Happy Confluence of Winter Books

It is 10 below zero here today, and I just finished the perfect book to read when it is this cold. It also occasioned one of those happy confluences when a favorite children’s book suddenly appears in adult form and is equally good. I have probably read Winter Cottage by Carol Ryrie Brink 30 or more times. Of course I had discovered Caddie Woodlawn and Magical Melons and then Two Are Better Than One and Louly by third grade, but then when I discovered Winter Cottage, something about it made it my favorite of her books.

It is 10 below zero here today, and I just finished the perfect book to read when it is this cold. It also occasioned one of those happy confluences when a favorite children’s book suddenly appears in adult form and is equally good. I have probably read Winter Cottage by Carol Ryrie Brink 30 or more times. Of course I had discovered Caddie Woodlawn and Magical Melons and then Two Are Better Than One and Louly by third grade, but then when I discovered Winter Cottage, something about it made it my favorite of her books.

I finally had a name for the reason after I read The Poetics of Space in college, and recognized what Gaston Bachelard called “intimate immensity” or the sheltered, small, hidden space that allows the spirit to roam freely. Bachelard’s contention is that such phenomena are ontological and that we experience them when a writer is able to express them for us. I experienced intimate immensity when I read Winter Cottage.

I finally had a name for the reason after I read The Poetics of Space in college, and recognized what Gaston Bachelard called “intimate immensity” or the sheltered, small, hidden space that allows the spirit to roam freely. Bachelard’s contention is that such phenomena are ontological and that we experience them when a writer is able to express them for us. I experienced intimate immensity when I read Winter Cottage.

The protagonist is Araminta Sparks, called Minty, who is on her way to Chicago with her sister Eglantine (Eggs) and their father Pops. It is the midst of the Depression, and their car breaks down on a back road they have accidentally turned onto. They find a summer cottage on a lake and “break in” to spend the night. Because they are hauling all the canned goods from Mr. Sparks’ failed grocery store, they eventually decide to winter there, planning to leave “rent” for the landlords whom they do not know.

Moving on to North of Hope. I had discovered the Loyola Classics series in Fall of 2008, and after I bought and read In This House of Brede, I made it known that I would like several more from the series. My lovely husband bought me three for Christmas last year, including North of Hope because Andy knows I like books about hardship, cold, Native Americans, and Catholics. Besides, look at that cover. Is that not lovely?

When the weather turns cold and nasty here, I usually pull out The Shipping News or Alistair MacLeod’s Island to make me count my blessings, but this year I picked up North of Hope. (I would also suggest Peace Like a River in this grouping). Jon Hassler is new to me, but I am now going to run out and read more of his books. He was a high-school English teacher and then taught college, later becoming Writer in Residence at Saint John’s University in Minnesota.

When the weather turns cold and nasty here, I usually pull out The Shipping News or Alistair MacLeod’s Island to make me count my blessings, but this year I picked up North of Hope. (I would also suggest Peace Like a River in this grouping). Jon Hassler is new to me, but I am now going to run out and read more of his books. He was a high-school English teacher and then taught college, later becoming Writer in Residence at Saint John’s University in Minnesota.

North of Hope focuses on Father Frank Healy, a priest having a crisis of not so much faith, as hope. He returns to his hometown parish to sort this through and is reunited with his best friend/almost girlfriend from high school Libby, who, though not religious, is similarly facing a crisis of hope as she deals with her manic-depressive daughter, drug-dealing doctor husband, and her own rekindled passion for Frank. These two spend a winter supporting each other through some true tragedies, and find in each other’s Platonic love and support, the means to find hope once again.

Reading Winter Cottage on a cold day is like drinking hot cocoa with marshmallows. Reading North of Hope was like drinking very strong espresso with maybe a shot of whiskey: adult, realistic, true, bitter, and yet still warming. The epistle from this morning’s Mass readings was from First Corinthians: “When I was a child, I used to talk as a child, think as a child, reason as a child; when I became a woman, I put aside childish things.” As a woman I have not totally put aside childish things; I still read the Little House books and I still read Winter Cottage. As a child, these books were an escape into another world, a rural, character-building place I wanted to be. And when I reread these books now, they do rekindle that romantic, adventurous feeling that inspired me as a girl.

But now I LIVE in that world, where things are rural and character-building, and I cherish the tales of adults facing these hardships with courage and integrity. Frank Healy is my grown-up Minty Sparks. The other time I had a similar book confluence was when I discovered Willa Cather’s Prairie Novels and had found the adult equivalent of Laura Ingalls Wilder. Alexandra Bergson is now my role model as much as ten-year-old Laura was.

In addition to the tough weather-beaten and life-beaten heroes I sought, I was also looking for books that created that “intimate immensity” of a small, warm, protected place in the midst of the snow and the chaos and the hardship. I think even as a kid I kind of knew that life could be a tough journey, and I girded my loins by finding heroines who took it on bare-handed and adult characters who provided safety and warmth. There is Pops at left, making his famous pancakes. That kitchen is warm, and light, and smells good. At right is Pops playing chess by the fire. It’s cold outside, and Minty’s mom is dead, and they have no home or money, and yet they have made a place of safety.

In addition to the tough weather-beaten and life-beaten heroes I sought, I was also looking for books that created that “intimate immensity” of a small, warm, protected place in the midst of the snow and the chaos and the hardship. I think even as a kid I kind of knew that life could be a tough journey, and I girded my loins by finding heroines who took it on bare-handed and adult characters who provided safety and warmth. There is Pops at left, making his famous pancakes. That kitchen is warm, and light, and smells good. At right is Pops playing chess by the fire. It’s cold outside, and Minty’s mom is dead, and they have no home or money, and yet they have made a place of safety.

In North of Hope that place of safety and warmth is much more abstract, in the way that adult things are. One character dies when his car goes through the ice, another is hospitalized in a mental clinic, another comes close to throwing herself in front of a train. There are no places of comfort for many of these characters. Frank has to find that place inside himself, as do the other troubled characters in the book. Most of them feel North of Hope itself, and hope IS that warm place by the fire. The hard thing in adulthood is creating that Winter Cottage metaphorically. And within.

Patty Hearst, my new BFF

I have a new colleague at work this year. We have lots in common: we are the same age, we both have three boys at home, we both teach these bizarre hybrid courses. But in many ways, we could not be more different. She is tall and blond; I am short and brown-haired with glasses. Her husband owns the country club; my husband owns a dairy farm. She is very organized; I am … not.

I have a new colleague at work this year. We have lots in common: we are the same age, we both have three boys at home, we both teach these bizarre hybrid courses. But in many ways, we could not be more different. She is tall and blond; I am short and brown-haired with glasses. Her husband owns the country club; my husband owns a dairy farm. She is very organized; I am … not.

But here’s the most startling difference. The other day she referred to her husband as “the morning guy” in terms of kid duty. And then she described him: He goes to work out at the YMCA at 5:30 AM, comes home, makes coffee and brings my colleague a cup in bed, gets their kids up, makes them a big breakfast, gets them out the door, and then cleans up the dishes. My colleague has come downstairs by this point to join them for breakfast and say goodbye. Her husband leaves for work, my colleague takes a shower and heads to work herself. (NOTE: take her job and add to it five English classes, and that’s my job.) She is a gracious and lovely person and said she was so grateful that she could stay home and raise their kids and wait to find a job that she really loves.

For a typical day in MY life, please refer to Tuckered-Out Duck: A Day in My Life.

Now, let’s assume that F. Lee Bailey was speaking the truth and that Patty Hearst was brainwashed by her kidnappers into joining the Symbionese Liberation Army. And let’s also imagine that on April 15, 1974, she for some reason snapped out of it and found herself in the middle of the Hibernia Bank heist.

Now, let’s assume that F. Lee Bailey was speaking the truth and that Patty Hearst was brainwashed by her kidnappers into joining the Symbionese Liberation Army. And let’s also imagine that on April 15, 1974, she for some reason snapped out of it and found herself in the middle of the Hibernia Bank heist.

I imagine her suddenly looking around, looking down at herself holding an M-1 carbine, and saying “What the …”

That is exactly how I felt during this conversation, as if I suddenly snapped out of my 20-year relationship with My Favorite Aspie and found myself saying “Wait … THAT’S a normal marriage? What the heck is this that I’m doing?”

I am sure other people also wonder that as they look at my weird life. Every once in a while someone witnessing my husband and me together will give me pointed looks as if to say, “You don’t have to live like this. There are places you can go” or alternately “I don’t know how you put up with him.” I have actually had people say that exact sentence to me, and I have given them the innocent questioning face, as if to say, “What? All’s normal here.”

I had a similar “What the …” when I read Home Safe over the summer. WARNING: NT wives with AS husbands, do NOT read this book, especially if you are a wannabe writer. Read every other thing Elizabeth Berg has ever written but avoid this one at the risk of anaphylactic shock.

I had a similar “What the …” when I read Home Safe over the summer. WARNING: NT wives with AS husbands, do NOT read this book, especially if you are a wannabe writer. Read every other thing Elizabeth Berg has ever written but avoid this one at the risk of anaphylactic shock.

Now, I truly adore Elizabeth Berg. I eat her books like pancakes off a stack. And I have seen her in person: she is lovely and gracious and her books are all warm-hearted and magnanimous and read so smoothly it’s like drinking the best ever cup of cocoa in book form, but I just about threw Home Safe across the room in despair.

The basic plot is this: The protagonist is a successful writer who, for the twenty years of her marriage, has every day rolled out of bed and to her computer in her pajamas to write while her husband takes care of EVERYTHING ELSE. As the book starts, she has been a widow for almost a year (I truly was saddened by this) and she is trying to get herself restarted. She suddenly finds out that her husband has taken a big chunk of their investments and purchased a house in California, which he has had custom-redesigned and redecorated in order to create exactly what he knows is her dream house, right down to the bookshelves filled with all her favorite children’s books, a fieldstone fireplace, a pie safe, a six-burner stove, a bathroom with artisan tiles and a shower with its water falling over a rock ledge, French doors leading from bedroom to garden, a small wooden shed outside for writing, a treehouse shaped like a ship’s cabin.

I’ll stop there before I cry. First, I fully recognize how much I have personally given up to make the dream of the farm come true (giving up any of my writing ambitions in the process), so this protagonist’s pre-widowhood life is beyond my imagining. Second, it is astronomically far outside the realm of possibility for Andy to know and create my dream house. It’s not his fault; it’s the Asperger’s: limited Theory of Mind ability, limited empathic response, and whimsy regarded always as unnecessary and illogical not to mention inefficient.

In thinking about this recently, I know there are several very logical reasons why it took me so long to really realize that something was a bit amiss and that our marriage situation was somewhat askew.

REASON ONE: Kid Sister Complex

I am the youngest of my family, younger by five years than my sister and younger by seven years than my brother. I grew up as the little tag-along, always clueless, always mocked, always sure that EVERYONE knew more about how to act and what to do than I did.

Andy is seven years older than I am. When I met him, I was going through a Linda Ronstandt phase, of the Nelson Riddle Orchestra “What’s New” album era, and I was constantly crooning “I’m a little lamb who’s lost in the wood, I know I could, always be good, to one who’ll watch over me.” Yep, looking for a father/big brother figure. I confess it. And so I always assumed Andy knew better. He was much older. He was an A-Dult and I was a kid. I followed his lead. Easier and cheaper to paint every single interior wall off-white? I guess so. Every once in a while I would cock an eyebrow and question something, but rarely. I figured, Older is Wiser.

Andy is seven years older than I am. When I met him, I was going through a Linda Ronstandt phase, of the Nelson Riddle Orchestra “What’s New” album era, and I was constantly crooning “I’m a little lamb who’s lost in the wood, I know I could, always be good, to one who’ll watch over me.” Yep, looking for a father/big brother figure. I confess it. And so I always assumed Andy knew better. He was much older. He was an A-Dult and I was a kid. I followed his lead. Easier and cheaper to paint every single interior wall off-white? I guess so. Every once in a while I would cock an eyebrow and question something, but rarely. I figured, Older is Wiser.

REASON TWO: Dysfunctional Family

REASON TWO: Dysfunctional Family

I also grew up in a dysfunctional family, loving but influenced heavily by alcoholism. I knew my family was not normal. I avoided bringing people to my house. I did not talk about what was happening at home. And I therefore saw all other families as infinitely more normal than my own. My in-laws, therefore, seemed paragons of normal. After all, they were both medical professionals, had a nice house and a vacation home, recreated with other adults, cooked gourmet meals. My family did none of these things. I assumed I was marrying into an incredibly normal WASP family and would be immersed into normal by means of their eldest progeny. Any choice of Andy’s I assumed to be normal with a capital N.

REASON THREE: The Farm

REASON THREE: The Farm

We knew, walking into the agricultural world, that nothing in our lives would be quite like other college graduates’ lives. Also, Andy was the Ag major. I was English/Art. I knew nothing about farming (besides what I had gleaned from the Little House books) and that meant that whatever I was told about anything related to the farm I took at face value. Also, we did nothing but work and worry for fifteen years. Work and worry, worry and work. Our situation economically and ergonomically was so outside the norm that all other components of it – including our marriage relationship – were assumed part of the lifestyle marginality. Work from 3:30 AM until 9 PM seven days a week? Normal, considering the circumstances. Constantly do things for the farm, never the house? Normal. Every cow problem a fatal catastrophe? Must be. Him’s the Ag major.

REASON FOUR: Isolation

REASON FOUR: Isolation

We are isolated here. I mean isolated. The long days, the far-away family, the lack of time for friends, the ten-mile drive to town, the five-mile neighbors. We had no real reflection of our lives in the eyes of friends or family, no one to pull me aside later and say, “Uh, Mo? Is everything alright?” Our families did this sporadically (Andy’s mother even said to me once “I do NOT like the way Andrew speaks to you”), but much of the odd behavior I was able to explain away by the omnipresent stress of starting the farm.

REASON FIVE: Stockholm Syndrome

REASON FIVE: Stockholm Syndrome

This one’s a stretch, but worth examining. According to the net’ s most reliable source of information, Wikipedia, Stockholm Syndrome explains an abductee’s or hostage’s love and loyalty toward his or her captor. The psychological explanation is that people will not allow themselves to remain unhappy for long because it causes cognitive dissonance. To resolve the dissonance, the person psychologically manipulates herself into being happy in the situation in which she finds herself, i.e. “I LOVE my captor. I CHOOSE to be under his control.” The other explanation likens the psychological strategy as akin to newborn attachment phenomenon. It is wise to attach to the nearest source of food and warmth since survival depends on it. And so, I was grateful for any let up in the endless grind. “My husband let me sleep in until 5 this morning! Isn’t he kind!”

But, there’s hope. I did find out about Asperger’s and can now differentiate between AS behavior and normal behavior. All this reading and breaking out of the NT-AS thang has liberated me from my blinders. Yeah, I’ve ruffled some Aspie feathers, but there’s a lot at stake here, especially my sanity.

Here’s Patty Hearst after her release from the Symbionese Liberation Army, with her former body guard, then fiance. Look how stinkin’ happy she looks! And look at that man – Is he going to ask her to lift a finger? No way. It’s going to be all about Patty. You go, girl! If you’re going to have a man with a gun glued to your side, make him not a captor but a bodyguard. And remember, you might have to be the one explaining to him which one to be.

A Book Review for Epiphany Sunday

TS Eliot’s poem “Journey of the Magi”

TS Eliot’s poem “Journey of the Magi”

A cold coming we had of it,

Just the worst time of the year

For a journey, and such a long journey:

The ways deep and the weather sharp,

The very dead of winter.’

And the camels galled, sore-footed, refractory,

Lying down in the melting snow.

There were times we regretted

The summer palaces on slopes, the terraces,

And the silken girls bringing sherbet.

Then the camel men cursing and grumbling

And running away, and wanting their liquor and women,

And the night-fires going out, and the lack of shelters,

And the cities hostile and the towns unfriendly

And the villages dirty and charging high prices:

A hard time we had of it.

At the end we preferred to travel all night,

Sleeping in snatches,

With the voices singing in our ears, saying

That this was all folly.

Then at dawn we came down to a temperate valley,

Wet, below the snow line, smelling of vegetation;

With a running stream and a water-mill beating the darkness,

And three trees on the low sky,

And an old white horse galloped away in the meadow.

Then we came to a tavern with vine-leaves over the lintel,

Six hands at an open door dicing for pieces of silver,

And feet kicking the empty wine-skins.

But there was no information, and so we continued

And arrived at evening, not a moment too soon

Finding the place; it was (you may say) satisfactory.

All this was a long time ago, I remember,

And I would do it again, but set down

This set down

This: were we led all that way for

Birth or Death? There was a Birth, certainly,

We had evidence and no doubt. I had seen birth and death,

But had thought they were different; this Birth was

Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death.

We returned to our places, these Kingdoms,

But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation,

With an alien people clutching their gods.

I should be glad of another death.

In this poem TS Eliot gives voice to the mysterious kings who, once they have seen the infant Jesus, return home unable to not completely change their outlook on life and religion. Yet they do not mourn this loss of old certainties, insisting they are happy to be shed of obsolete beliefs. The Magi were led to experience this world-view revolution by the words of a prophet, what Flannery O’Connor called a “realist of distances,” one who can describe in detail what is yet to come because of lucid understanding of what currently is.

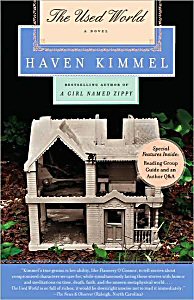

In Quaker writer Haven Kimmel’s fictional gem The Used World, Hazel Hunnicutt, proprietor of the eponymous Used World Emporium, is such a prophet. She sees what is distant by discerning the purest essence of what is and urging it into new combinations. Her most significant “arrangement” in the novel, and what drives the plot, involves her two employees: 40-something Claudia Modjeski, a six-foot-four androgynous woman living alone and mourning the death of her beloved mother, and 20-something Rebekah Shook, disowned by her Pentecostal father after she becomes pregnant by her first-ever lover, the decidedly non-Pentecostal Peter. This new arrangement also involves a baby boy, “stolen” after being orphaned into the meth-addicted biker gang Hazel’s own sister has fallen into, as well as a pit bull, abandoned by and rescued from the same.

In Quaker writer Haven Kimmel’s fictional gem The Used World, Hazel Hunnicutt, proprietor of the eponymous Used World Emporium, is such a prophet. She sees what is distant by discerning the purest essence of what is and urging it into new combinations. Her most significant “arrangement” in the novel, and what drives the plot, involves her two employees: 40-something Claudia Modjeski, a six-foot-four androgynous woman living alone and mourning the death of her beloved mother, and 20-something Rebekah Shook, disowned by her Pentecostal father after she becomes pregnant by her first-ever lover, the decidedly non-Pentecostal Peter. This new arrangement also involves a baby boy, “stolen” after being orphaned into the meth-addicted biker gang Hazel’s own sister has fallen into, as well as a pit bull, abandoned by and rescued from the same.

The new story that is created here is ingeniously formed by Kimmel from elements of the old. Narration of the present-day lives of the main characters is interspersed with chronologically presented flashbacks to Hazel’s childhood and early adulthood. In these scenes Hazel, who early in life is “marked” for prescience by an owl, learns to differentiate between those acts that demonstrate pure love – though they might not be socially accepted – and “antique” traditions that deserve casting off when what they produce is pain and suffering. Hazel’s past and present circumstances call for quite challenging acts of discernment, from evaluating her mother’s work with unwanted pregnancies and her own repressed love for her best friend to the proper response to her sister’s addiction and to a fledgling lesbian relationship. Kimmel does not portray these acts of discernment as easy, nor should she. She opens such perennial powder-kegs as illegitimacy, homosexuality, and abortion, all flash-points that persist throughout human history, elicit changing societal responses as humanity evolves, and remain controversial because they are so complex.

The “theological” opinions voiced in the book contrast Rebekah’s father Vernon, a member of The Prophetic Mission where “the cruel, the stupid, the kind and the good alike believed they were the conduits for the direct revelation of Yahweh,” and Amos Townsend, pastor of the Church of the Brethren. The principle difference between these two is the degree of certainty with which they assert their beliefs. Where Vernon Shook continually reaffirms his own incontestable convictions, Amos humbly questions his own claims even from the pulpit. While Amos mistrusts the idea that anyone can thoroughly understand Jesus and so speculates more than pontificates, he does avow those truths he knows to be everlasting, especially the truth that God is Love and is revealed through love.

Throughout the book, in both image and theme, Kimmel contends there is much in life to preserve because it is good, but there is also much that should not be clutched merely because it is old. Acts of loving responsibility, symbolized by Claudia’s mother’s preserves and Rebekah’s mother’s recipes, shine out against the micro-waved meals of Claudia’s married-with-children sister Millie and the immature instant-message romance of the self-centered and two-timing Peter. These two, dubbed the New Mother and the New Man, have left the past completely behind but have also, unfortunately, abandoned those elements that were most worth saving.

On the other hand those who cling too fiercely to their outdated beliefs – Vernon and Hazel’s father Albert – leave destruction in their wake when the “truths” they cling to are divisive, vindictive, self-serving, and intolerant. Those characters unwilling or unable to sort the treasure from the junk are left to suffer at their own hands, while those who adapt and move on, doing what love asks of them, thrive and grow. Kimmel challenges us too to retain what things are true, honest, just, pure, and lovely but to also be open to the new and sometimes unexpected ways these can be combined. The only test, and every great agape practitioner from Saint Francis to Dorothy Day would agree, is the question What is love asking of us now?

Haven Kimmel, whose hysterically funny memoir A Girl Named Zippy launched her onto the New York Times Bestsellers List in 2002, employs the same down-home humor in The Used World. But here in the world of fiction, Kimmel can employ even more nuance in her craft. Her symbolic touch throughout is simultaneously subtle and ever-present. The novel can simply be enjoyed as a gripping tale and yet the watchful reader discovers constant nuggets of pure philosophical gold, just as the persistent antiquer consistently finds new treasures in her favorite store. For example, the epigraph for Part Two from Luke, “the child in my womb leaped for joy,” literally describes Claudia’s reaction to the arrival of the pregnant Rebekah but also posits these two as a modern-day Elizabeth and Mary. Even such Judeo-Christian mainstays as a flood, a mob called Legion, and a woman saltily looking back read as seamless plot elements, especially as they are mixed with non-Biblical archetypes such as an Old Road, animal familiars, and three-headed dogs.

And this is indeed Kimmel’s point. There is only one story, one rock of permanence, one eternal word, and that is compassion. The impermanent and ever-changing face of history’s artifacts should not be worshipped. If the Word Himself calls us to anything it is to caritas, in whatever unusual and unexpected combinations this might require. It could be an illegitimate baby born to country folks in a stable and worshipped by royalty. It could be a woman accepting the love of another woman and raising a stolen child. The Magi say that what looks to be birth turned out to be death. And in The Used World what looks to be death turns out to be birth. The suicidal Claudia, the maltreated infant Oliver, the exiled Rebekah, the frantically despairing Millie and even the still-bereaved Hazel find new life in the odd arrangement a blizzard in Indiana hurls into place. As Hazel says, “There is wild change afoot, and you must be brave enough to not only endure it, but to embrace it, to make it your own.” And to do so, Kimmel maintains, always with compassion.

From “Winter Barley” by Andrea Lee

The Storm

Night; a house in northern Scotland. When October gales blow in off the Atlantic, one thinks of sodden sheep huddled downwind and of oil cowboys on bucking North Sea rigs… even a large solid house like this one feels temporary tonight, like a hand cupped around a match. Flourishes of hail, like bird shot against the windows; a wuthering in the chimneys, the sound of an army of giants charging over the hilltops in the dark…

Halloween

Bent double, Edo and Elizabeth creep through a stand of spindly larch and bilberry toward the pond where the geese are settling for the night. It is after four on a cold, clear afternoon, with the sun already behind the hills and a concentrated essence of leaf meal and wet earth rising headily at their footsteps – an elixir of autumn… Now from the corner of the grove, Edo and Elizabeth spy on two or three hundred geese in a crowd as thick and racuous as bathers on a city beach: preening, socializing, some pulling at sedges in the water of the murky little pond, others arriving from the sky in unraveling skeins, calling, wheeling, landing….

A tumult of wind and dogs greets them as they pull up ten minutes later to the house. Dervishes of leaves spin on the gravel … Both Elizabeth and Edo stare in surprise at the kitchen windows, where there is an unusual glow. It looks like something on fire, and for an instant Edo has the sensation of disaster – a conflagration not of this house, nothing so real, but a mirage of a burning city, a sign transplanted from a dream…

Elizabeth sees quite clearly what Nestor and his cousins have done and, with an odd sense of relief, starts to giggle. They’ve carved four pumpkins with horrible faces, put candles inside, and lined them up on the windowsills… “It’s Halloween,” she says, in a voice pitched a shade too high…[Edo] hurries inside, telling her to follow him.

Instead, Elizabeth lets the door close and lingers outside, looking at the glowing vegetable faces and feeling the cold wind shove her hair back from her forehead… she thinks of a Halloween in Dover when she was eight or nine and stood for a long time on the doorstep of her own house after her brothers and everyone else had gone inside. The two big elms leaned over the moon, and the jack-o’-lantern in the front window had a thick dribble of wax depending from its grin…She’d stood there feeling excitement and terror at the small, dark world she had created around herself simply by holding back.”

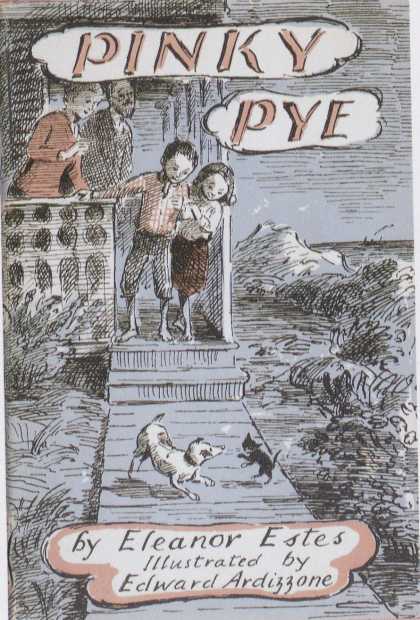

I went through a series of many years when I snatched The Best American Short Stories volumes off the New Books shelf at the library as soon as they arrived. Now, not so much. The 1993 edition came out in the midst of my Louise Erdrich jag, and since she was editor that year, I very much snagged and devoured. I was VERY struck by the short story “Winter Barley” by Andrea Lee, not so much for the plot but for the setting and the mood.

A week ago I made the very old librarian go down and retrieve 1993 for me from the basement (I offered to go down there myself, but that is where the very secret books are kept, like A House Like a Lotus by Madeleine L’Engle. What? because of the lesbianism?) and I reread this story and was again transported. This story has taken the place of Mr. McFadden’s Halloween* and The Halloween Tree in my repertoire of seasonal , transporting books. So above are my favorite chunks with some visuals to go along.

This story was originally published in The New Yorker and can be read (if you are a digital subscriber) here.Or you can get the 1993 edition of The Best American Short Stories. Here is the New Yorker’s abstract:

“Elizabeth, 30, a banker from Massachusetts who is stationed in Rome, and Edo, 60, an exiled prince from an Eastern European kingdom now extinct, have an affair at his home in Scotland. They meet at Easter. Elizabeth is invited to Scotland by Edo’s gay nephew, Nestor, her neighbor in Rome. Nestor doesn’t show up, having deliberately planned to throw the two of them together. Edo regales her with anecdotes about his world travels, and challenges her with his snobbery. They become lovers, although Elizabeth does not feel that she is in love with Edo. She is bored by his interest in water fowl; he has designed his estate to attract them. At Halloween, Nestor and two aristocratic friends arrive in Scotland. They and Edo try to offend Elizabeth with bawdy songs and stories. Edo is annoyed when the young men surprise him and Elizabeth by putting jack-o’-lanterns in the windows. Elizabeth has a childhood memory of Halloween in Dover, Massachusetts. Edo recalls an experience in Persia, when two of his friends, Persian princes, surprised him in the desert, bearing falcons.”

According to Andrea Lee’s Contributor’s Note in BASS, she was inspired by a line at the end of King Lear where Lear and Cordelia plan to escape together and enjoy “an improbable idyll” of father-daughter love. Lee wanted to replicate such an idyll in a modern context and so devised a “father-daughter” love affair. Why did an image of Michael Douglas and Catherine Zeta-Jones just jump into my head?

According to Andrea Lee’s Contributor’s Note in BASS, she was inspired by a line at the end of King Lear where Lear and Cordelia plan to escape together and enjoy “an improbable idyll” of father-daughter love. Lee wanted to replicate such an idyll in a modern context and so devised a “father-daughter” love affair. Why did an image of Michael Douglas and Catherine Zeta-Jones just jump into my head?

Ray Bradbury's painting of The Halloween Tree

Happy Halloween, everyone!

* Speaking of Rumer Godden, I have lately discovered her adult novels. (I was a huge fan of her middle grade books: Mr. McFadden’s Halloween, The Doll‘s House, The Story of Holly and Ivy, Miss Happiness and Miss Flower, The Kitchen Madonna). I am now enjoying In This House of Brede about Benedictine nuns. Next on my list is Five for Sorrow, Ten for Joy. Both of these are part of the Loyola Classics series. More on that later. Check her out at left with her cats. The website for the Rumer Godden Literary Trust is wonderful.

* Speaking of Rumer Godden, I have lately discovered her adult novels. (I was a huge fan of her middle grade books: Mr. McFadden’s Halloween, The Doll‘s House, The Story of Holly and Ivy, Miss Happiness and Miss Flower, The Kitchen Madonna). I am now enjoying In This House of Brede about Benedictine nuns. Next on my list is Five for Sorrow, Ten for Joy. Both of these are part of the Loyola Classics series. More on that later. Check her out at left with her cats. The website for the Rumer Godden Literary Trust is wonderful.

The Catcher in the Rye

For your listening pleasure while you are reading this post, here is the Count Basie Band (my dad’s favorite) playing Comin’ Through the Rye.

This is a photograph of my maternal grandmother, Mabel Ruth Kellick, in her teens. Whenever she showed me this photo, she would always say, “Mabel, coming through the rye.”

One of my three books waiting to get published (Who am I kidding? I am waiting for an agent to discover me and wrangle one of them into something salable) is called “Wonderful Plans of Old.” It starts with a family intervention to deal with the father’s alcoholism, and then goes backwards and forwards in time to explore the roots of this moment as well as the effects after it. When I was writing it, I was reading the Book of Isaiah, because it seemed to fit so well with the ideas of Desolation and Redemption I was exploring in the book, and each chapter title is taken from Isaiah. This chapter is from the very middle. Don’t worry: I will be tying all this seemingly random stuff together!

Among Fat Ones, Leanness

Kate was gone to China – we rarely heard from her. Patrick was home sometimes, six weeks at college followed by six weeks of working at home. And I was a high school senior: pianist, valedictorian, tennis team captain, and so very alone. My English class read The Catcher in the Rye that year, and like all adolescents I felt that Holden Caufield was my voice: repulsed by all the phoniness of adulthood and reluctant to move into the contradictions it seemed to mandate.

I rode the bus home from school, sitting in the front seat with a scarf over my nose and mouth to filter out the smoke – not all of it tobacco – that drifted from the back of the bus. Our driver was known to allow – even condone – smoking, so the bus was packed with students willing to walk ten blocks home from the wrong stop to smoke their pot in warmth for one mile. Roxie the bus driver would snap her gum, big ball earrings bobbling, and cackle to the back, “You smokin’ that horse shit back there?” She purposely aimed for the big bump halfway down Washburn Street and we would all fly into the air. Everyone but me laughed.

When I got dropped off, I walked across the street, got the spare key from the garage, and let myself in. No one was home. I’d drop my books at the kitchen table, take off my coat, and start the ritual. Holden had a malted and grilled cheese at the soda fountain. Without the equipment of a diner, I made do with a cheese sandwich on toast and a chocolate milkshake. Then I would line up twenty-five Ritz crackers – five by five – and slather them with peanut butter. Once I had eaten those, I checked into the ice cream – usually half of a half gallon would go next. Then Oreos: one column. By then my stomach felt tight, way beyond Holden and into a territory of loneliness Holden did not know, a territory where no one saw me, no one knew what I was doing, where no one seemed to notice that I was home, wanting someone to care about my day, wanting someone to notice that I had emotionally quit everything.

The upstairs bathroom was the place: away from anyone, close the door, turn on the fan, run the water, pretend I was a teenage girl obsessed with washing my face in case anyone got home early. No one knew – or really cared – what I was doing, even when I repeated this part of the ritual right after dinner. It really became quite easy. I would drink an enormous glass of water, and then it was amazing how easily it all came out – it didn’t even taste bad, just a watered down version of what I had just eaten. Three times and it was all out. I had had the feast – treated myself if no one else would – and still did not gain weight – as thin as a Junior Miss at least. So thin that my period stopped and Mom finally took me to an endocrinologist who took one look at me and said, “She’s too thin.”

I got thin, very thin, and I would lie in the hot June sun in the driveway on the lawn chair wearing only the Bloomies underwear and camisole I had bought on a class trip to New York City, the camisole rolled up to expose my browned stomach. I had no bikini and Mom wouldn’t allow one, but my blue-and-pink-striped cotton undies worked the same, as long as I had covered up by the time Mom got home. Our backyard was shaded by a huge maple, but there was a strip of strong sunlight along our driveway right next to the Gardiner Girls’ lilac bushes, which were on the other side of the waist-high chain link fence.

Mrs. Dixon came over one day and found me this way. I didn’t hear her approach since I had my Walkman on, slathering myself with coconut oil. “It must be nice to be so perfect,” she said, looking down her nose at me. She obviously disapproved of a teenage girl half dressed lying in view from Morton Avenue, or else she was jealous – a former beauty queen herself, believe it or not – whose figure with teenage children now was not what it had been.

I smiled in a knowing adolescent way and pulled my sunglasses back down over my eyes. If only boys would have the same response, but my obsession with my weight was mixed with a fear of sex, and the physiological effects of thinness had been to halt my hormones, leaving me desireless. I craved the jealousy of my female peers more than attraction by males. I wouldn’t have known what to do with a boyfriend if I had one.

The night of my first drink, I had gone to a senior dinner dance with a childhood pal, and there, in a funky bar in Buffalo, I had several white Russians. They tasted good, and I enjoyed, for a time, the way I warmed up, chatted with everyone, danced without inhibitions. But on the way home I felt bad, guilty, headachy, and when I crashed into my room that night, I planned the next morning to confess and gain absolution from my parents.

When I finally awoke, a beautiful, sunny spring day, my head ached, and I lumped down the stairs to the kitchen where my father was making a second pot of coffee. I slumped into a chair and drank the glass of orange juice he offered.

“How was the dance?”

“OK, I guess.”

“Did Jeremy behave?”

“Barely.” I finished the orange juice and poured some more.

“Where’s Mom?” I asked. “Aren’t you guys going to church?”

Dad sat down across from me and took a deep breath, sighed long.

“Mom’s upstairs in her room.”

I looked up. Something had happened.

“She had to have her stomach pumped last night.” I stopped. I had a vision of an ambulance in the driveway, reds lights flashing on the neighbors’ houses and on the Sansones’ garage wall. Mom on a gurney coming out the front door.

“She … wanted to show me what I looked like, so she drank an entire bottle of wine.”

I felt sick to my stomach. “Is she OK?”

“Yes. She’s going to be OK. She’s resting upstairs.”

“Can I go see her?”

He nodded.

I got up, holding my throbbing head, and went into the living room and up the stairs to the second floor. Across the hall I could see that the door of the sewing room where she had been sleeping of late on the spare bed was shut. I approached it quietly and peeked in through the crack. She had her eyes closed, but she heard me at the door and opened them.

“Hi, Moll. You can come in.”

I opened the door, which squeaked a little, and closed it behind me. The lovely soft sun had risen and came in a strip under the shades on the east window. I moved slowly to the bed and sat down on the edge.

“How are you feeling?” I asked.

“Kind of bad,” she whispered. “Did Dad tell you?”

“Yes.”

“I’m sorry. On the night of your date.” She cleared her throat, which appeared to be a painful process. “How was it?”

“It was fine. Do you need anything?”

“No.”

“Can I lie down with you?” She made room, turned over and faced the wall. I lay down on top of the blanket and spooned in next to her, like she used to do with me when I was scared by a nightmare, but our positions were reversed. I put my arm around her and just stayed. The shade glowed with the sunlight outside, but in her darkened room it felt more like sunset.

She was there through the next two weeks, up until my graduation. Dad called and told her boss that she was very sick. After school I would come home and lie with her. Then I would go back downstairs and sit at the table, doing my homework: Calculus, AP Bio, English, Psych – a breeze really, it just took time – and maybe I would play the piano, or practice my valedictory address, or I would take the car and drive to the school a few blocks away and practice my forehand, hitting my tennis ball against the big brick wall, over and over and over and over until blisters formed and broke open and my hands bled.

Did the music end? Here it is again.

Did the music end? Here it is again.

I would not wish such a senior year on my worst enemy. Unfortunately, many students in high school DO have this kind of senior year. I have been teaching seniors now for eleven years, and I am convinced that it is one of the most stressful and difficult years of a kid’s life. It is like Kindergarten in reverse. Kindergarten means leaving the safety of home for the unknown of school; senior year involves leaving not only the now thoroughly known of school, but also leaving hometown, everyone known and loved for 18 years of life, and heading into the unknown of adult life.

Yes, some students are Homecoming King or Queen and apply early decision and are accepted at their first choice college, with a happily married mom and dad standing proudly behind them. But plenty of others are dealing with a parent’s illness or divorce or a major family problem, they have suffered socially throughout school and are glad to be leaving it behind, though they are simultaneously terrified of the blank slate before them. Sometimes no one has ever seen or understood their situation, and they have no support at all as they apply to colleges, all the while knowing that there is no money available at home to support this huge and expensive venture.

These kids need a catcher in the rye. They are technically adults, and yet many of them are running dangerously close to a cliff’s edge. Oddly enough, I have found myself in a job where I can BE the catcher in the rye for some of these kids. In my previous teacher job, I saw 75 kids a day for 40 minutes each: they were a blur. Because I now have a small class of students and see them for over two hours a day, my relationship with them is very intense and becomes very close. I know their lives and their dreams. Also, the programs that my colleagues and I run require students to leave the safety and familiarity of their home schools and take an early leap into independence and novelty. We often end up with the kids who are happy to be leaving their high schools behind.

These kids need a catcher in the rye. They are technically adults, and yet many of them are running dangerously close to a cliff’s edge. Oddly enough, I have found myself in a job where I can BE the catcher in the rye for some of these kids. In my previous teacher job, I saw 75 kids a day for 40 minutes each: they were a blur. Because I now have a small class of students and see them for over two hours a day, my relationship with them is very intense and becomes very close. I know their lives and their dreams. Also, the programs that my colleagues and I run require students to leave the safety and familiarity of their home schools and take an early leap into independence and novelty. We often end up with the kids who are happy to be leaving their high schools behind.

Because I was also one of these types, I find myself with a rare ability to see their fears and their hurts, and I find myself so grateful to be in a position to help them, to the best of my ability. To quote Holden, my main man,

“I keep picturing all these little kids playing some game in this big field of rye and all. Thousands of little kids, and nobody’s around – nobody big, I mean – except me. And I’m standing on the edge of some crazy cliff. What I have to do, I have to catch everybody if they start to go over the cliff – I mean if they’re running and they don’t look where they’re going I have to come out from somewhere and catch them. That’s all I’d do all day. I’d just be the catcher in the rye and all. I know it’s crazy, but that’s the only thing I’d really like to be. I know it’s crazy.”

Not crazy, Holden. I hear you, dude. Many of us have fallen off that cliff because no one was there to catch us. But anyone who has been over that cliff can see – preternaturally almost – those heading toward the edge. You can see it in their eyes, in their stance, in their words or their silence. If you personally survive the fall and pick yourself back up, you are in a unique position to see those little kids nearing the edge and to try to get in the way.

My heart aches for the Holdens and the Mollys of the world, and the many real teenagers I have seen undergo this process. My heart aches because it ached for me going through it. Holden sobs for Phoebe in her joy on the carousel, and it is true that innocence – either in its still pure form or lost through no fault of the child – is worth our sobbing over. The events that cause this are often beyond anyone’s control; who can stop cancer or death or any of a variety of things from raining on our parades? But I wish here to offer thanks that I have been given the opportunity to see and assuage what pain I can. God grant me the wisdom and the strength to do so.

Carousel by Leeanne McDonough as found at http://dazzioart.com/

Trolling for Chinook on Lake Ontario

Here is a movie of the trip Andy, Elliot, and I took on Lake Ontario. This is Andy at his very happiest – fishing.

(Elliot gets the credit for the ending footage of waves.)

The song is “Wave Over Wave” by Great Big Sea, a band that I love from Newfoundland. All the guys in the band are Irish, Canadian, English majors, and play hockey. Could you ask for more? The guy on the left is Alan Doyle (sigh) who will be in the new Robin Hood movie to be released next year. He is at his most charming in this video of Great Big Sea and the Chieftains singing Lukey’s Boat. My second choice would be Sean McCann, playing bodhran: so stinkin’ cute.

The song is “Wave Over Wave” by Great Big Sea, a band that I love from Newfoundland. All the guys in the band are Irish, Canadian, English majors, and play hockey. Could you ask for more? The guy on the left is Alan Doyle (sigh) who will be in the new Robin Hood movie to be released next year. He is at his most charming in this video of Great Big Sea and the Chieftains singing Lukey’s Boat. My second choice would be Sean McCann, playing bodhran: so stinkin’ cute.

But of course neither one is as charming as my hubbie!

Blogging: The Introvert’s Ultimate Yop!

I recently finished reading Patrick O’Keeffe’s collection The Hill Road, named after the first of the four novellas it contains. I was entranced. O’Keeffe is a professor of Creative Writing at Colgate and was the instructor for the short fiction workshop at the Colgate Writers’ Conference I attended. I had the good fortune of hearing him read from a new work and then meeting him afterwards on the last full day of the conference.

I recently finished reading Patrick O’Keeffe’s collection The Hill Road, named after the first of the four novellas it contains. I was entranced. O’Keeffe is a professor of Creative Writing at Colgate and was the instructor for the short fiction workshop at the Colgate Writers’ Conference I attended. I had the good fortune of hearing him read from a new work and then meeting him afterwards on the last full day of the conference.

I bought his book after the reading, partly because I loved the cover painting called Cottages of Connemara.Two years ago, when I workshopped my novel Wonderful Plans of Old, my group’s favorite chapter was one in which I had imagined an evening in the life of my Irish great-grandparents, and I had set it outside Connemara in Ireland. I have never been to Ireland, nor while I was growing up did I ever hear stories of life in Ireland before my ancestors emigrated. For that matter, I never heard stories of my father’s childhood here in New York. He NEVER spoke about it, leaving me to conjure what I could out of references, imagination, questions, pictures.

What struck me so about O’Keeffe’s collection was how each of the four novellas dealt with this very issue: the task of trying to piece together a story which had never been told, or was only told in snatches under influence of drink or grave illness, leaving me wondering if this trait of Not Talking is endemic in the Irish people. Think of Alice McDermott’s novel Charming Billy, the twisting, winding story of a lie and its truth which had been kept long secret.

Is this tendency Irish? Is it a defense mechanism for any group that has withstood great hardship and dire acts taken out of necessity or despair? Is the same true of Holocaust survivors? former soldiers? Are there certain experiences that are simply too painful for the psyche to bear telling?

My dad after my wedding, Zeke in the background

Or perhaps the common link, one which ties me to my father, is the Irish tendency toward contemplation. My father’s most characteristic pose was standing with weight on one foot, the other resting in front at an angle or up on something, one hand in pocket, the other leaning on a counter or windowsill, gazing. He would spend long periods of time this way. He did not speak much, but I learned to listen very intently when he did speak, for what he had to say was well worth listening to, forged as it was out of these long periods of contemplation.

My dad was an introvert, which is probably why he wanted to become a writer. He had plenty to say, he just didn’t like to talk. I am the same way. In seventh grade, my Home Economics teacher was Mrs. Williams, a.k.a. “Wimp Williams” because she was so soft-spoken. The most upset she ever got was when we were sewing and students would slam down the presser foot on the sewing machines. She would close her eyes, hold out one raised hand in gentle protest, and say with valiantly restrained anger, “Don’t. Slam. the Presser Foot.” And then we would all keep doing it. (I am really sorry, Mrs. Williams).

She told my parents at a parent/teacher conference that she could see I was “keeping my light under a bushel.” When I heard this, I thought to myself, No, I am just not about to cast my pearls before swine. The problem was that if I actually verbalized what I was thinking, my classmates would have thought me even stranger than they already did. It’s not that the teenaged swine would snout my pearls around in the muck but that it would be ME – my deepest self – that they were knocking through the crap. More emotional pain? Nein, danke.

Also, I truly do not like to talk. The physical act of getting my thoughts to slow down enough to verbalize them, of pushing these ethereal things out through the thick clay of my tongue and lips, and not being able to edit words that have floated out into the air, makes talking one of the last things I like to do. I’d rather write.

Thus my gratitude for the tremendous gift of blogging, and I am guessing this is the case for many introverted bloggers. We’ve got things to say. We’ve got thoughts worth sharing. And we are not afraid to cast them out over the wide waters of the internet. But let it be just my WORDS, in print, no sign of me, my face, my squeaky weird voice.

And not only that, but blogging is also ART. You create a visual product with colors and pictures and even MOVIES. It is like my thoughts – both word and image – incarnated digitally.

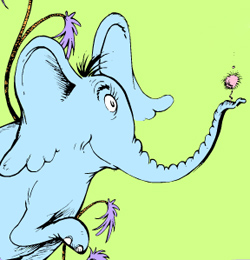

Like the little Who whose “Yop!” finally stops those awful monkeys from boiling that dust speck, introverts need a lot of effort to make noise, but we will do it. And in our long periods of thoughtfulness, we sometimes come up with ideas from which other people can benefit. So, what do I write when I write? I tell my thoughts. I tell the secrets of my childhood. I tell the secrets of my marriage. This is beyond Yop! This is doing what I was raised not to do.

Like the little Who whose “Yop!” finally stops those awful monkeys from boiling that dust speck, introverts need a lot of effort to make noise, but we will do it. And in our long periods of thoughtfulness, we sometimes come up with ideas from which other people can benefit. So, what do I write when I write? I tell my thoughts. I tell the secrets of my childhood. I tell the secrets of my marriage. This is beyond Yop! This is doing what I was raised not to do.

Any child of an alcoholic grows up with the unstated but implicit rule “Don’t tell.” Don’t tell what happens at home. Don’t say how you really feel because no one is really there to hear you. But I have learned, against my familial tendencies, to “tell tales.” Why? First, because I have experienced how silence harms: how not speaking, not communicating your shame or fear or anxiety can cause real damage.

Perhaps I read so much as a kid because in authors I found the words to describe what I was not allowed to say out loud, what I never heard anyone one else say out loud, what was difficult for me to say out loud. And hearing from someone else, in another place, thoughts that I had had, made me see I was not alone, I was not so strange, that there were others out there with similar thoughts and problems and ideas.

Last week I was thinking about this in church and we sang this song:

A lovely painting by blogging artist Jennifer Katheiser

I myself am the bread of life.

You and I are the bread of life.

Taken and blessed,

broken and shared by Christ

that the world might live.

Lives broken open,

stories shared aloud,

becomes a banquet,

a shelter for the world:

a living sign of God in Christ.

This is the second reason I tell my tales. If this is what we are to be – broken and shared that others might live – then the introvert is obligated to share what she is and what she has: her thoughts, her life, her stories, not as recrimination but as a banquet, an offering of those thoughts and experiences in order to console others by letting them see in print their own deepest and perhaps un-worded thoughts. At least that is what I hope to do, give voice to all those weird and profound and silly thoughts that too many people keep under a bushel.

So thanks, all you blogging introverts out there who are letting your voices be heard, and thanks, WordPress, for letting me Yop! Reader, if you find any pearls here, please help yourself, and feel free to cast your own pearls as comments.

Girl Meets Elephant

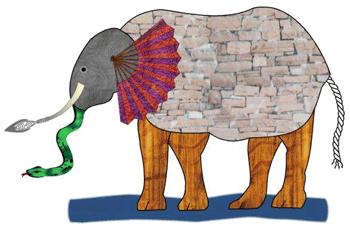

Well, a certain commenter has got me thinking about religions and denominations and world views, and at the risk of blabbing my theories all over the internet (but isn’t that what blogging is all about?), I would like to share this poem by John Godfrey Saxe, which is actually a re-telling of a Hindu myth:

It was six men of Indostan

To learning much inclined,

Who went to see the Elephant

(Though all of them were blind),

That each by observation

Might satisfy his mind.

The First approach’d the Elephant,

And happening to fall

Against his broad and sturdy side,

At once began to bawl:

“God bless me! but the Elephant

Is very like a wall!”

The Second, feeling of the tusk,

Cried, -“Ho! what have we here

So very round and smooth and sharp?

To me ’tis mighty clear

This wonder of an Elephant

Is very like a spear!”

The Third approached the animal,

And happening to take

The squirming trunk within his hands,

Thus boldly up and spake:

“I see,” quoth he, “the Elephant

Is very like a snake!”

The Fourth reached out his eager hand,

And felt about the knee.

“What most this wondrous beast is like

Is mighty plain,” quoth he,

“‘Tis clear enough the Elephant

Is very like a tree!”

The Fifth, who chanced to touch the ear,

Said: “E’en the blindest man

Can tell what this resembles most;

Deny the fact who can,

This marvel of an Elephant

Is very like a fan!”

The Sixth no sooner had begun

About the beast to grope,

Then, seizing on the swinging tail

That fell within his scope,

“I see,” quoth he, “the Elephant

Is very like a rope!”

And so these men of Indostan

Disputed loud and long,

Each in his own opinion

Exceeding stiff and strong,

Though each was partly in the right,

And all were in the wrong!

MORAL.

So oft in theologic wars,

The disputants, I ween,

Rail on in utter ignorance

Of what each other mean,

And prate about an Elephant

Not one of them has seen!

When my children ask me about religion, I always tell them this story about the elephant.

My own zig-zag spiritual path has involved encounters with each of the following:

1 Raised Post-Vatican II Catholic, including the spiritual renewal of the 1980s

2 Assembly of God during high school, including a summer working at an AOG camp and a mega-conference during which I evangelized using the four spiritual truths

3 Living in Japan with a family who practiced the combination of Buddhism and Shinto typical of the Japanese

4 A nameless church that met in homes

5 Collegiate studies in comparative religion that introduced me to Taoism, Buddhism, Judaism, Hindu, Confucianism, etc.

6 Marrying basically a pagan (in the best sense of that word)

7 Discovery of the Catholic mystics

8 Continued reading in a variety of religious traditions: chakras, Kabbala, whatever I run into that feels like Truth.

I hope that where this has finally landed me is in the camp of humility at my inability to understand what is really going on. I fully acknowledge that I am a blind woman running into various parts of an enormous elephant that I am unable to see. I think it is very possible that each of the world’s religions taps into a pure vein of what is the ineffable divinity at the heart of the universe. I KNOW it is very possible that we really haven’t a clue, and that if we WERE to experience the divinity in its resplendent form, that our nervous systems would not be able to handle the load.

In terms of EXPRESSION of spiritual experience and outward communication of and participation with community in spiritual life, I fall back on the experience of Christmas in my hometown. Lockport, New York, was settled by immigrants from Ireland and Italy who found work in America digging the Erie Barge Canal. Because so many settled in Lockport, the city has always been predominantly Catholic. However, there is quite a difference between the Irish-Catholic traditions and the Italian-Catholic traditions.

Take Christmas for example. In my house, we ate potatoes and roast beef and opened one gift on Christmas Eve listening to Nat King Cole and drinking eggnog. Imagine my surprise to find out that my Italian friends had the Feast of Seven Fishes on Christmas Eve. What?! Fish!? That’s not Christmas!!!!!

But I am absolutely convinced that the feeling of Christmas in each household is the same. Family. Food. Gifts. Magic. Mystery. Light in darkness. What specific food and music is involved is beside the point. And some people grow up on roast beef, discover the seven fishes through a spouse, and have suddenly found their celebratory home.

Now, if sacrificing small children is what it takes for you to be singin’ and swingin’ and gettin’ merry like Christmas, I am probably going to have a problem with that, in the same way that “killing the American he-devils” might make me think twice about Jihadist Islam or stockpiling weapons to prepare for Armageddon makes the Branch Davidians seem not quite aligned.

But I cling to “by their fruits ye shall know them,” and I keep reminding myself that it is a very large elephant and I am a grasping blind woman. The shelf of “Bibles” that make me feel aligned is large and eclectic. The very fact of Thomas Merton and the Dalai Lama makes me feel God. The art of Sher Fick makes me feel God. The novels of Haven Kimmel make me feel God. The poetry of Elizabeth Bishop makes me feel God.

I am completely open to being told I am wrong about all this. Therefore, I would welcome a discussion here. Feel free to agree, disagree and/or throw in some new ideas of your own.

Down the Up Staircase

For many years after we moved to our farm in rural upstate New York, I had a recurrent nightmare that I had not really graduated from Amherst College. In the dream I would be my waking age of 24, eventually 30 and later still 37, and yet I would have to return to Amherst for three more semesters, leaving my husband and child – then later two and three children – back at home. In most cases the dream began mid-semester, and I was very behind in my Religion course, owing a paper I had not yet started, nor had I even attended the class, leaving me unable to even start it.

This dream, needless to say, bothered me quite a bit, so much so that I dug out my Amherst diploma and my Phi Beta Kappa key and placed them prominently above my desk to remind me that I really HAD graduated. I also hung my Master’s diploma and my permanent high-school teaching license. But this did nothing to stop the dreams, which continued to recur once a month or so.

I am sure my mother and father, watching me receive my Amherst diploma in 1990 and then leave Massachusetts with my fiancé to buy a farm in Central New York, must also have wondered if I had really graduated. Or if I had, with a degree in what? Tractor Operation?

My father had grown up in Western New York, youngest child of second-generation Irish immigrants on both sides, on a small farm, hating it. He hated killing chickens and he hated milking the cow and he hated the No Irish Need Apply stories he had heard, and so he embraced America – the jazz and the City, and he dreamed of nights in a Harlem club, ringed in cigarette smoke, writing. Thanks to the GI Bill, he had just matriculated at Columbia’s Journalism school when his father’s death put an end to his dreams. He instead attended nearby Canisius College, studied accounting, cared for his widowed mother, landed a post in the GM executive building, and married the sparkling platinum blonde at the water cooler.

My father had grown up in Western New York, youngest child of second-generation Irish immigrants on both sides, on a small farm, hating it. He hated killing chickens and he hated milking the cow and he hated the No Irish Need Apply stories he had heard, and so he embraced America – the jazz and the City, and he dreamed of nights in a Harlem club, ringed in cigarette smoke, writing. Thanks to the GI Bill, he had just matriculated at Columbia’s Journalism school when his father’s death put an end to his dreams. He instead attended nearby Canisius College, studied accounting, cared for his widowed mother, landed a post in the GM executive building, and married the sparkling platinum blonde at the water cooler.

Meanwhile, my mother had also moved up in the world, from the ten-year-old whose mother (my grandmother) had snatched her and her brothers from beatings by her alcoholic father and evictions from apartment after apartment and had found respect caring for the children of the well-to-do, and my mother grew to become a popular high-school socialite. Later, with her high-school secretarial diploma in hand, she spent two years working at the Vatican and then returned to Western New York, the world-traveler and eye-catcher in the secretarial pool at the radiator plant.

Helped by America’s post-World-War-II prosperity and GM’s solid position in the Big Three, my parents managed to gain a firm toe-hold in the middle class, with a house and car and three healthy children. Even so, my mother always feared her own exposure as the sole non-college-graduate at Mothers Club, and my father’s unspoken dreams and unwritten books eddied around our feet like discontented waves in that house on Harrison Avenue.

We three children all felt it and sought to climb beyond the middle-class staircase landing, especially when our academic shining also served to blind others to the dark issues muddying the dull glow of the existence my parents had hacked out of their respective pasts. The Irish genes carried intelligence as well, and my siblings and I had a clear and unobstructed path to most any college we chose and beyond. My sister eventually earned a PhD and a prestigious educational consulting job, and my brother added an MBA to his engineering degree to move far above my dad in the GM hierarchy. By the mid-80s we all three were riding the up escalator of the rising middle-class.

In 1985 I was catapulted from my GM hometown into Central Massachusetts to land among the nation’s elite at Amherst. A veritable conspiracy of forces had propelled me there. In 1980 The Official Preppy Handbook hit my junior high school like contraband. We Italian and Irish immigrants’ children, still virtually loam-footed from digging the Erie Canal, pored over this book like a National Geographic full of naked bushmen, as stunned and confused by what we saw as by Papua New Guinea’s painted tribes.

In 1985 I was catapulted from my GM hometown into Central Massachusetts to land among the nation’s elite at Amherst. A veritable conspiracy of forces had propelled me there. In 1980 The Official Preppy Handbook hit my junior high school like contraband. We Italian and Irish immigrants’ children, still virtually loam-footed from digging the Erie Canal, pored over this book like a National Geographic full of naked bushmen, as stunned and confused by what we saw as by Papua New Guinea’s painted tribes.

Oddly enough, my best friend that year was suddenly plucked out of our canal town by the remarriage of her divorced mother to a movie magnate in DC. Her new life bestowed upon her a stone mansion in Georgetown and attendance at a prestigious all-girls prep school. She was the real thing, not the pseudo-preps my friends and I were at Lockport Senior High School in our K-Mart Oxford cloth shirts and Dickies.

The three prongs of that mighty trident – parental dreams, best-pal jealousy, and my own intellectual inheritance – prodded me to apply to the Little Ivies, and the Amherst acceptance clinched it by topping 1983’s US New and World Report listing of Top Liberal Arts Schools. The world was my oyster, and I was invited to sit smack in the middle of that pink cushiony mollusk.

However, something happened once I got there. Very few people are able to analyze their own historical context clearly, much less a young woman way out of her league among peers who were comfortably inheriting positions at the top of the heap. I was so stimulated by the rarefied intellectual atmosphere that I did not recognize the signs of decadence and over-consumption that were sweeping the national economic landscape and intensifying my culture shock.

Once the novelty of it all wore off, some underlying sense of unease set in. I am sure I stuck out like a sore thumb at Amherst; after all, it was not hard for me to pick out the other scholarship/work-study students. I remember my shame at how easily my name was forgotten or never learned by my wealthier classmates. I remember one in particular who wore his Exeter legacy like his own skin and another who co-opted our student art exhibition into her own personal soiree. I was shocked by this, though moral indignation took a back seat to intimidation and insecurity.

Nevertheless, by the time I met, fell in love with, and accepted the marriage proposal of a UMass Ag School graduate in my junior year, I was quite happy to turn around on the lingerie floor and take the down escalator past my parents and even further down, to our economy’s basement: farming. It is true I had fallen in love with an Ag major, and it is true that he was also a borderline Marxist, but it is also true that the chance to buy a farm and work very hard at manual labor struck a deep and resonant chord already vibrating within me, where law school or marrying a future Wall Street executive did not.

It wasn’t until years later, when I ran into Dr. Ruby Payne’s 1998 Framework for Understanding Poverty, that my subconscious collegiate reasoning was clarified. In the public education world, Dr. Payne’s theory is used to explain why it is so difficult to help students rise out of generational poverty. Personally, I was not so much struck by the “hidden rules” of the lower class (which engulfed me both in rural Central New York and my hometown) as I was by articulation of the hidden rules of the upper class, which I had divined in college but not previously seen articulated so clearly. This very prize had been right there, tantalizingly just inches beyond my fingers, and I could have quite easily ridden that late-Reagan/early Clinton wave right into fortune and luxury, but I did not. There was something in that glittering mirage that turned my stomach, that made me turn around, that made me run down that up staircase as fast and as far as I could.

It wasn’t until years later, when I ran into Dr. Ruby Payne’s 1998 Framework for Understanding Poverty, that my subconscious collegiate reasoning was clarified. In the public education world, Dr. Payne’s theory is used to explain why it is so difficult to help students rise out of generational poverty. Personally, I was not so much struck by the “hidden rules” of the lower class (which engulfed me both in rural Central New York and my hometown) as I was by articulation of the hidden rules of the upper class, which I had divined in college but not previously seen articulated so clearly. This very prize had been right there, tantalizingly just inches beyond my fingers, and I could have quite easily ridden that late-Reagan/early Clinton wave right into fortune and luxury, but I did not. There was something in that glittering mirage that turned my stomach, that made me turn around, that made me run down that up staircase as fast and as far as I could.

Dr. Payne differentiates among the three sets of “rules” followed by the generational poor, the middle-class, and the wealthy with regard to seven different value sets. In terms of possessions, the poor focus on relationships, the middle-class on material items, and the wealthy on one-of-a-kind objects, legacies, and pedigrees. With food, “having enough” is the hidden rule for those in generational poverty, “quality” is important to the middle class, while the wealthy focus on “aesthetic presentation.” Regarding fighting, the poor resort to physical means, the middle-class to discussion, and the wealthy to social exclusion and lawyers. The poor focus on present time, the middle-class to planning for the future, and the wealthy to preserving past history and traditions. While the poor base their acceptance of others on liking, and the middle class judges a person’s achievements and success, the wealthy consider connections and social standing.

Of course these are generalizations and the many exceptions mock any indication of this theory’s irrefutability, but reflecting back on my Amherst days, this theory resonated with my own take on the unspoken social forces that caused me considerable unease in college, even granting the excesses of the era. I saw and heard and experienced these rules that guide the wealthy, and I turned and walked away from them. Social exclusion, preservation of tradition and legacies at the expense of justice, social standing as more important than people – these were not values I was raised with, and they were not values I aspired to adopt.

My husband and I chose instead one of the hardest rows to hoe, literally, and have sacrificed literal blood, sweat, and tears to dig our way out of the debt required to buy, equip, and stock a dairy farm. And yes, I felt foolish sometimes, and yes, that subconscious need to return and “finish” my Amherst degree seemed to indicate my doubt that I was right to turn and descend, my underlying sense that I had missed something that Amherst could have taught me about success and comfort and the easier life. Perhaps I just needed a few more semesters to get used to the idea.

The current economic downturn, however, has turned this all on its head. Even the middle-class status my family fought to attain appears to be crumbling. My older brother, whose GM division was sold to Delphi, just lost the retirement health insurance he had worked 40 years to earn. My mother’s generous widow’s pension is in question as GM itself has just teetered into bankruptcy. Many of my fellow 80s grads moved to the Bright Lights, Big City and became Less Than Zero, and the Wall-Street-bound might very well now be without work. Furthermore, the wider world, through the basics of supply and demand – is stealing away, at lower-but-welcomed wages, the very jobs that formerly bought us our large houses and multiple cars and weight problems.

I heard recently that in 2006, the average income of the country’s 400 wealthiest people was $263 million – each. Had it been $263 million total, that would still have been over $657,000 each – surely more than enough. But no, it was $263 million each. This meant that the wealthiest 1% of the population took home 22% of the national income. Picture a room in which there are 100 loaves of bread. One hundred people enter the room and ONE person takes 22 of the loaves for himself, leaving the other 99 hungry to split up the remaining 78 loaves. One person gets 22 loaves; the others each get less than four-fifths of one loaf. That’s the number 22 compared to .78. Would anyone want to admit to being that person? I would not, especially if this amassing of wealth was in the name of “preservation of tradition” to allow for “aesthetic presentation” and “social standing” won through “social exclusion and lawyers.” Hello, my name is Mephistopheles.

Now that two decades of economic growth and over-consumption are coming to a screeching halt, I would love to credit myself with prescience, but I think it was something more like a good grasp of reality. In the environmental world, exponential growth is simply not possible. A species’ population will grow until it exceeds the ecosystem’s carrying capacity, at which point it will drop off. A parasite will thrive only until its host sickens unto death. Even in the nursery school playroom, the other children will ignore the child who takes two toys, but when that same child takes ten toys, the scene devolves into Lord of the Flies.

Now that two decades of economic growth and over-consumption are coming to a screeching halt, I would love to credit myself with prescience, but I think it was something more like a good grasp of reality. In the environmental world, exponential growth is simply not possible. A species’ population will grow until it exceeds the ecosystem’s carrying capacity, at which point it will drop off. A parasite will thrive only until its host sickens unto death. Even in the nursery school playroom, the other children will ignore the child who takes two toys, but when that same child takes ten toys, the scene devolves into Lord of the Flies.