Limiting Exercises

I am still basking in the afterglow of the Colgate Writers’ Conference, which I attended this past week. I had the great privilege of being in a novel workshop led by Brian Hall, whose intelligence, generosity, humor, insight, and talent cannot be exaggerated. I read his novel The Saskiad last month, and his novels Fall of Frost and I Should Be Extremely Happy in Your Company are now on the top of my teetering pile of summer reading. I will also be adding his book Madeleine’s World: A Biography of a Three-Year-Old to my Education Professions curriculum next year.

In addition to the intensive workshop, I also attended the Craft Talks by other incredibly talented and generous writers: Jennifer Brice, Jennifer Vanderbes (my workshop instructor two years ago – You must read her novel Easter Island), Peter Balakian, J. Robert Lennon, and Patrick O’Keeffe. Their craft talks will be available on the Colgate Writers’ Conference website this summer. Past years’ talks by many of these same writers are already there and are a rare and invigorating treat.

In addition to the intensive workshop, I also attended the Craft Talks by other incredibly talented and generous writers: Jennifer Brice, Jennifer Vanderbes (my workshop instructor two years ago – You must read her novel Easter Island), Peter Balakian, J. Robert Lennon, and Patrick O’Keeffe. Their craft talks will be available on the Colgate Writers’ Conference website this summer. Past years’ talks by many of these same writers are already there and are a rare and invigorating treat.

My fellow workshop attendees were also a treat and shared their incredible talents as we workshopped their novels- and memoirs-in-progress. Two of our original group of five were unable to attend, and so we had Thursday and Friday mornings to do with as we chose. On Thursday we did an exercise, which I will describe in a moment, and on Friday two of us workshopped other chunks of manuscripts-in-progress.

As always when talking or hearing about the writing process, I was struck several times by the idea of writing as metaphor for life. Perhaps everything is metaphor for life, or perhaps, as the Kabbalists believe, all physical phenomena are essentially divine energy diffused into an infinite myriad of manifestations. Or maybe, as I am starting to believe, everything is a fractal, everything, if looked at in closer and closer magnification, is seen to be made up of smaller and smaller versions of itself.

One writing technique that was discussed in particular gave me plenty to think about in terms of both writing and life as I know it. This was the idea of the Limiting Exercise.

I encountered this idea during college in another wonderful Nathan Margalit class called Methods and Materials. One assignment we were given was to take a famous painting and spend … a week? two weeks? (I don’t remember) doing nothing but art based on that work. I chose Vermeer’s Young Woman with a Water Pitcher and created 15 variations, each more surprising to me than the last.

Later, in my teaching life, I was attempting to have my tenth-graders write poetry, and realized that given no parameters, the choices were too endless and my non-poet students were, for the most part, writing schlock. Remembering my Art background, I pulled out my prints of Monet’s haystack series and explained to my students that I was going to give them a similar limitation to force their creativity.

I assigned a sestina, a very restrictive seven-stanza poetic form, invented in the 12th century and still used today by poets. I discovered this form in college when I read The Complete Poems of Elizabeth Bishop, whose Sestina is one of the most-often anthologized examples of the form. The summer after my friends and I finished college, we all spent the summer writing these while house-sitting in the Montague hills (ah, English majors).

This form restricts the poet to only six end words, rearranged over the course of seven stanzas in a very specific order. As soon as I restricted my students in this way, they began writing much more powerful and beautiful stuff. My sister ended up doing dissertation research for her PhD in Cognitive Psychology on using examples to teach writing by “teaching” the sestina in my tenth-grade classes.

As we discussed in our Colgate workshop, it is common practice for writers to set themselves certain restrictions any time they write: point of view, for example. Do I choose first person or third person? If third person, then omniscient or limited or polyvalent? (a new word to me this week) Once the choice is made, that to a large extent imposes restrictions on the text.

However, for the exercise we did, Brian imposed a VERY limiting rule, so limiting that all of us in the workshop were paralyzed for a few moments, and as we worked you could hear grunts and growls of exasperation as we found ourselves roadblocked every other word: we were to write about a funeral without using the letter “e.” Here is what I came up with – without the help of a thesaurus!

On my way down stairs grimy with dirt, I stop and try my ducts for salt, for liquid, for signs that what awaits within will call from my past’s dim rooms any salt or sting. Finding only “dry” and “blank” in locations from which any squall or storm might tug, I walk toward a door I would turn from if I could, but approach anyway, finding it pulls my body through.

Within, a hush of lights and aromas surround that I most avoid. Aunts and trailing husbands, boys and girls, dumb with discomfort, old grandma sitting on a dais at a lost captain’s prow, surround a box I avoid at all costs.

I hug my mom, my dad. I slowly wind a circuitous path through bumbling cousins who touch or murmur what might sound sad but actually roars, low and ominous.

Shalimar and Coty’s L’aimant swirl in battling soft clouds. Mascara, lipstick, suits long hung in musty bags, skirts and shirts in vibrant colors stab at trying on “valor” or “joy” or any mood that adds a coat of familial gloss to what lurks in sharp looks or harsh coughs or pointing hands that sign out a grim truth.

I finally draw up to that obligatory black coffin and scan that craggy chin and high brow, cold now to my touch as always it was in mood glaring my way.

When I read it back, I realized that most of what I wrote I would NEVER have normally written. My ideas had to come out through some others space, like Play-Doh coming out the sides when the sliding shape-maker of the Fun Factory is plugged up.

On Friday morning, J. Robert Lennon shared in his public Craft Talk a number of limiting exercises as well as examples of what he had written when he had given himself these exercises. Check these out on his website: The Cat Text had me crying with laughter as did his New Sentences for the Testing of Typewriters as did his disquisition on the website I Can Has Cheezburger? which is a big favorite in our household. The image to the left was my son’s desktop picture for months. The writing parallel comes from being forced to use kitten grammar, ala lolcats speech.

In our workshop right afterward, we workshopped my essay Ah-Ha! Moment: The “Diagnosis”. In addition to some very helpful writing feedback, I also got, as I often do in regard to living with Asperger’s, “How do you do it?” “How can you live with this?” and “Doesn’t this sometimes just drive you crazy?” On a bad day, my answers to these questions would be “Not with much grace” and “Some days it’s really hard” and “Yes.”

Later in the day these two things overlapped in my head and I thought to myself, Marriage to an Aspergian: The Ultimate Limiting Exercise, which of course could also be the subtitle for Life as a Dairy Farmer.

Sure, Asperger’s imposes certain limitations, but doesn’t every marriage? Marry a PhD in History and you are probably fated to moving from university to university waiting for tenure. Marry a lumberjack and you will be living near forests. Marry someone with diabetes and you will be monitoring blood sugar.

Look what often happens when people HAVE no limitations: celebrity athletes worth millions go broke or commit crimes, kids who inherit enormous trust funds become alcoholics or addicts, Brad runs off with Angelina when obviously Jennifer was his soul mate (please don’t think that last was anything but ironic). Limitless money, limitless fawning men or women: people usually do not handle that situation well.

Benedictines often talk about the value of their vow of stability. Thomas Merton flopped around like a crazed dilettante until he committed himself to the most restrictive monastic order there is: the Cistercians. They do not leave the monastery and they do not speak. But look at what came out of him then. Perhaps Flannery O’Connor’s lupus forced her creative hand. Dorothy Day chose poverty, and her very life became her creation.

The Taoists have a saying that I frequently fall back on: One disease, long life. No disease, short life.

Having some sort of restriction forces us to act wisely within that restriction’s confines and to care for ourselves or our marriage or our art in purposeful, thoughtful ways. No restrictions allows us to live in perhaps too daring a way, putting ourselves in dangerous situations. Think of children: in the absence of restrictions they will touch hot stoves, jump into deep water, wander into traffic. Our son, as he has gotten older and we have allowed him a longer leash, has often run gratefully back into the fold when we have snagged him from some dangerous social precipice, at least until he hankers for another foray toward adulthood.

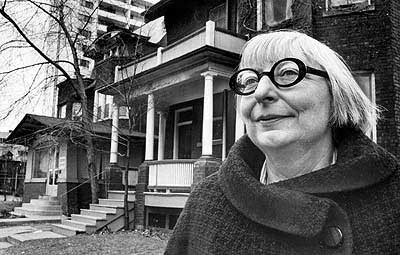

Jane Jacobs

My theory on this from a scientific standpoint is that our genetic code is hardwired for limitations because that is one of the natural laws: an ecosystem will expand and diversify until some limiting factor stops it at the system’s carrying capacity. There is only so much available to the system. As Jane Jacobs so brilliantly pointed out in her book The Nature of Economies, our human economies MUST function under the same laws because they ARE regulated by the same laws. Our economy is a fractal made up of the ecologies on which it is based.

All living beings are forced to survive in conditions of scarcity. Plants and animals do this by instinct or by trial-and-error or stimulus-response: Fly south — NOW. No food here → migrate. Not enough nitrogen → stop growing vegetatively.

We humans employ rational choice in a condition of scarcity. There is NOT an infinite amount of money or time or physical resources. You assess what you have, weigh the costs and benefits of each option, and choose accordingly. In the same way, we weigh potential spouses, look at the costs and benefits of each potential mate, and make our choice. (Can you tell the Asperger’s has rubbed off on me a bit? Read John Elder Robison’s memoir Look Me in the Eye for an Aspergian take on mate selection.)

Because we are rational, speaking beings, we have developed rituals that make public some of these rational choices. Marriage is one of the most significant limiting exercises we perform. That’s what the vows are all about: “forsaking all others, cleave thee only unto him as long as you both shall live.” That is a pretty serious limiting exercise right there, like writing using ONLY the vowel “e.”

Sure, Asperger’s imposes more restrictions than the normal marriage, and so does dairy farming. Wendell Berry talks about this in his essay “A Few Words for Motherhood.” As he helps a cow give birth, he thinks of Thoreau’s farmer-bashing words from Walden (which raise my hackles, too) and says that we all commit to something, even if it is to the idea of having NO commitments. Wendell Berry chose farm animals.

Sure, Asperger’s imposes more restrictions than the normal marriage, and so does dairy farming. Wendell Berry talks about this in his essay “A Few Words for Motherhood.” As he helps a cow give birth, he thinks of Thoreau’s farmer-bashing words from Walden (which raise my hackles, too) and says that we all commit to something, even if it is to the idea of having NO commitments. Wendell Berry chose farm animals.

I chose Andy, and Asperger’s came with the package. I could get all frustrated and kick and scream or leave, or I can accept the limitation and use it as an exercise in marital creativity.

If you are an artist or a writer, when you impose a restriction on yourself, the creativity gets squeezed out in other unexpected ways. Brian encouraged us to “look for unpredictable elegant opportunities” that happen in writing when we don’t dictatorially impose our own will on the text, that these often lead the text in a new direction that is BETTER than the original plan.

I choose to see my marriage that way. The Asperger’s has been a “restriction” that forced the writing of my own life into a very different direction. Perhaps the creativity this requires of me will make of my life something more creative, and maybe more beautiful, than what it might have been without that restriction.

This is what I love about reading good literary fiction: you can tell when the writers have allowed the texts to force their hand in a way, and have followed and shaped those sometimes unplanned restrictions into art. For my own tastes, I love when a writer or artist has made beauty out of real and sometimes difficult limitations. This is art that, because it is true, always rings true.

Please share your thoughts …..

Nightmare, or Mo Goes Goth

In college I took a class in Printmaking from the fabulous Nathan Margalit.

One exercise we did involved creating intaglio etchings by pressing a random assortment of cloths and other objects onto the waxy surface painted over the metal plate. Then we dipped the plates into acid, which burned into the lines where the cloth had removed the wax. We were then challenged to look for images in the random patterns and work with the intaglio process to create something from the shapes and forms left behind. I created several odd pieces of art using this process, one of which is above and the other below.

I realize just how much this process influenced my creative side – especially the act of starting from the random and seeing what the subconscious dredges up.

In my continuing series of short movies based on songs from Kate Bush’s The Ninth Wave, I offer the below film “Nightmare” which makes use of my intaglios of long ago.

Swimming in Lake Poison

This week I am attending the Colgate Writers’ Conference in Hamilton, NY. I was accepted into the novel-writing workshop along with three other participants, and our workshop instructor will be Brian Hall, author of the novels The Saskiad, Fall of Frost, and I Should Be Extremely Happy In Your Company: A Novel of Lewis and Clark, as well as several works of non-fiction. I attended this same conference two years ago and worked with Jennifer Vanderbes, author of Ester Island.

I will be workshopping a novel I started about five years ago, tentatively titled Swimming in Lake Poison. I partly used the painting below by John August Swanson as inspiration. I have posted Chapter One below, and would be grateful for any feedback.

I will share pictures and more from the conference once it is over. If you would like to join me vicariously, the public lectures – including each morning’s Craft Talk and each evenings Readings – are available at http://groups.colgate.edu/cwc/archive.html. This year’s will not be available until much later, but the previous year’s are also great. Especially, you should become familiar with Frederick Busch’s work if you are not already. I have read his novel Harry and Catherine probably fifteen times.

Chapter One

One night, during the worst of it, the week we kept the shotgun next to bed, the week we had to send the kids away, the week we slept holding each other for safety, I had this dream:

We were on vacation at our family camp, high in the Berkshires of Connecticut. But in the dream it was a much exaggerated version of Mount Riga, wilder, steeper, more densely forested, and poorer. There was no wealthy and manicured New England town at its foot. It seemed instead to be placed in the rural poverty of the wilder regions of the Northern Adirondacks or northern Vermont, far from where anyone with wealth or sophisticated aesthetics would summer. To arrive at this surreal version of our refuge required skirting a lumber town, a rough and bedraggled collection of old warehouses and greasy auto shops, furred by spruces, with that sinister feel of forests in the primitive Northwest, where the trees are angry ancients leaning over and threatening to swallow you in their growth.

Upon our arrival, my husband Ty’s family had already assembled, and the lake and A-frame and cabins seemed almost true to their wonderful, normal selves. All of my mother-in-law’s Swedish relatives had gathered, from all corners of the country, and although it appeared that the lake was very cold – thin sheets of ice laced its edges – young cousins, previously unknown to me, were swimming along its uneven and rocky shoreline. In the dream, unlike in the real Lake Riga, high, columnar islands of rock topped with shaggy pines rose not far from shore, and pallid Swedish boys, all of them young cousins and second cousins, dove in masks around their murky bases in the narrow area between islands and land, seeking gold or what would pass for it with younger relatives.

Almost immediately upon arrival, after hugs and introductions, Ty and I were dispatched to run an errand: to fetch an air mattress left at the lake’s other end, needed by one of the guests for sleeping on that night. Though I was tired and longed to crawl into a soft nest in our camper, Ty and I prepared to set out in the late afternoon with a flashlight to fetch it.

As we approached our vehicle to go, an extraordinary procession of young, male, white-robed acolytes proceeded along the sandy road under the low-hanging pines, carrying large white candles and singing. They walked slowly, a hundred or so of them, the flames lighting up their joyous faces, and as they passed, they looked at us and smiled as they sang, a slow meditative song full of plain harmonies, like chant or incantation. Everyone at our camp stopped in slow silence and smiled in their glow. The young monks walked toward their rustic monastery farther around the lake. The harmonies of their song drifted through the trees and echoed across the water.

Still, Ty and I had to fetch the mattress, and instead of taking a canoe or the Jeep, we set out on foot, back down the rough road and through the lumber town and further down the mountain and back into the scrubland forest to the lake’s other end. Peering under dense bushes with our flashlight, we found the raft under some brush on the dirt road’s side. The road we were on stopped at the lake’s edge seemed to have no other destination than this distant spot, and we wondered who had been here earlier in the day and for what reason, far from the main enclave and in so isolated a place. With the half-deflated plastic raft under my arm, we set out for the long walk back.

As we returned, ever-darkening twilight turned back to bright day, and our narrow path down through the open land suddenly rose to a high and thin-aired height, while the region to our right dropped, such that the houses and churches below looked like toys. The trees disappeared and we walked along an Alpine path, and the ancient and softened Berkshires turned to snow-topped mountain peaks and the land to our side sank into green-lined river valleys. Now that we were above the tree line, the evergreens of Connecticut shrunk to the short brush of the high peaks, and we walked the narrow ridge of a high mountain trail toward a tiny town perched on one crag. We stumbled over rocks on the narrow path, and I struggled with the burden of the raft.

The tiny town seemed to be holding its market day, and each of the handful of tiny kiosks stood in relief high against the Andean air, a small wooden cart or booth with bright scarves or hanging peppers blowing in the wind from its racks. Ty and I stopped at one, where textiles hung in a fury of color against the white sky. In the bright and wind-whipped air, we struggled to choose one and pay its seller, a short, compact man with brown skin and smiling eyes, with a band of brightly-striped wool over one shoulder.

We passed beyond his stand at the peak of the village, toward a one-room Alpine tavern on a steep and narrow ridge, where mountain men of foreign skins and languages sang and clanked heavy wooden mugs of some native grog. Ty stopped in to join them for a drink and I continued toward the small mountain lake ahead, holding by the hand the frailest of the Swedish girl cousins who was suddenly and inexplicably in my charge. Two nuns, in soft yellow habits and comfortably middle-aged faces in high peaked wimples, approached and smiled and nodded as they passed us. We nodded in return and continued on our way. I glanced down, far down into the valley, and saw, like a jewel in the green valley below, a perfect Austrian abbey, soft yellow, like a pound of creamy butter on its green lawns, with tall Baroque windows and topped with dark onion-shaped domes, a shiny copper cross atop each. It was a long building, with the central section most likely the dormitory, clean and airy, and the taller end with the most steeples the sanctuary. From its windows soared the measured tones of Gregorian chant.

We realized that the two nuns we had passed were most likely from there, and sure enough, when we turned to look where the two had gone, we could see them descending a gentle path that led down, down, down toward the picturesque little haven below. I watched, wanted to follow, stopped, until my little cousin tugged my hand and I turned to her and smiled and walked on.

She and I continued toward the lake ahead, and as we neared, we could see it had a sandy beach and shallow water for wading. Knowing we would have to wait for Ty, we stripped down to our bathing suits, leaving our clothes and shoes on towels on the beach, and waded in. It was a small and open lake, no more than five acres, more of a pond, and we could easily see across it to the rocky shore on the other side. My little cousin stayed wading in the shallow waters with sand beneath her feet, but I, hot and a swimmer by nature, dove under and headed toward the deeper and cooler water in the middle.

When I surfaced there and shook the hair and water from my eyes, I saw to one side of the pond a tall earthen dam through which opened an enormous corrugated metal culvert. I looked higher up and noticed the factory from which it came. Only then did I look down, to the water I was treading in, and see the noxious green ooze. I followed its liquid path to the culvert and saw the mix of green and phosphorescent orange that flowed toward me, foaming and scum-topped. The watery trail was dotted with thin metal scraps and shredded labels, plastic bung-hole caps and globs of brownish sludge.

I scrambled to turn in the deep water and head back toward shore, but the mire became viscous and I flailed to direct my body shoreward. I was gasping in panic and exertion and I feared gulping a mouthful of the sickly and putrid slime that circled my face. My skin was starting to smart and sting, and I swam in desperation toward shore, shouting for my little cousin to Get out! Get out! Pushing against the resistance of the thick water, my feet finally hit ground, and I slugged heavily, weighted down, toward my charge who was splashing and falling toward the beach.

Finally close enough, I grabbed her, flung us both onto the land, and dragged her to a water spigot where I quickly and viciously hosed her down. Luckily, only her legs were affected, and the green poison washed off. I was saturated: my skin, my hair, my arms and legs, my swimsuit, and though I sprayed and sprayed and pressurized the water against myself, the toxins burned and stung, and my skin was stained a sickly greenish-orange, and though I washed and scrubbed and directed the water full-force, I could not remove the poisons from my skin.

Girl Meets Elephant

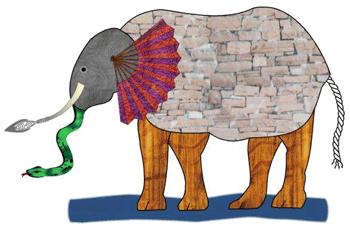

Well, a certain commenter has got me thinking about religions and denominations and world views, and at the risk of blabbing my theories all over the internet (but isn’t that what blogging is all about?), I would like to share this poem by John Godfrey Saxe, which is actually a re-telling of a Hindu myth:

It was six men of Indostan

To learning much inclined,

Who went to see the Elephant

(Though all of them were blind),

That each by observation

Might satisfy his mind.

The First approach’d the Elephant,

And happening to fall

Against his broad and sturdy side,

At once began to bawl:

“God bless me! but the Elephant

Is very like a wall!”

The Second, feeling of the tusk,

Cried, -“Ho! what have we here

So very round and smooth and sharp?

To me ’tis mighty clear

This wonder of an Elephant

Is very like a spear!”

The Third approached the animal,

And happening to take

The squirming trunk within his hands,

Thus boldly up and spake:

“I see,” quoth he, “the Elephant

Is very like a snake!”

The Fourth reached out his eager hand,

And felt about the knee.

“What most this wondrous beast is like

Is mighty plain,” quoth he,

“‘Tis clear enough the Elephant

Is very like a tree!”

The Fifth, who chanced to touch the ear,

Said: “E’en the blindest man

Can tell what this resembles most;

Deny the fact who can,

This marvel of an Elephant

Is very like a fan!”

The Sixth no sooner had begun

About the beast to grope,

Then, seizing on the swinging tail

That fell within his scope,

“I see,” quoth he, “the Elephant

Is very like a rope!”

And so these men of Indostan

Disputed loud and long,

Each in his own opinion

Exceeding stiff and strong,

Though each was partly in the right,

And all were in the wrong!

MORAL.

So oft in theologic wars,

The disputants, I ween,

Rail on in utter ignorance

Of what each other mean,

And prate about an Elephant

Not one of them has seen!

When my children ask me about religion, I always tell them this story about the elephant.

My own zig-zag spiritual path has involved encounters with each of the following:

1 Raised Post-Vatican II Catholic, including the spiritual renewal of the 1980s

2 Assembly of God during high school, including a summer working at an AOG camp and a mega-conference during which I evangelized using the four spiritual truths

3 Living in Japan with a family who practiced the combination of Buddhism and Shinto typical of the Japanese

4 A nameless church that met in homes

5 Collegiate studies in comparative religion that introduced me to Taoism, Buddhism, Judaism, Hindu, Confucianism, etc.

6 Marrying basically a pagan (in the best sense of that word)

7 Discovery of the Catholic mystics

8 Continued reading in a variety of religious traditions: chakras, Kabbala, whatever I run into that feels like Truth.

I hope that where this has finally landed me is in the camp of humility at my inability to understand what is really going on. I fully acknowledge that I am a blind woman running into various parts of an enormous elephant that I am unable to see. I think it is very possible that each of the world’s religions taps into a pure vein of what is the ineffable divinity at the heart of the universe. I KNOW it is very possible that we really haven’t a clue, and that if we WERE to experience the divinity in its resplendent form, that our nervous systems would not be able to handle the load.

In terms of EXPRESSION of spiritual experience and outward communication of and participation with community in spiritual life, I fall back on the experience of Christmas in my hometown. Lockport, New York, was settled by immigrants from Ireland and Italy who found work in America digging the Erie Barge Canal. Because so many settled in Lockport, the city has always been predominantly Catholic. However, there is quite a difference between the Irish-Catholic traditions and the Italian-Catholic traditions.

Take Christmas for example. In my house, we ate potatoes and roast beef and opened one gift on Christmas Eve listening to Nat King Cole and drinking eggnog. Imagine my surprise to find out that my Italian friends had the Feast of Seven Fishes on Christmas Eve. What?! Fish!? That’s not Christmas!!!!!

But I am absolutely convinced that the feeling of Christmas in each household is the same. Family. Food. Gifts. Magic. Mystery. Light in darkness. What specific food and music is involved is beside the point. And some people grow up on roast beef, discover the seven fishes through a spouse, and have suddenly found their celebratory home.

Now, if sacrificing small children is what it takes for you to be singin’ and swingin’ and gettin’ merry like Christmas, I am probably going to have a problem with that, in the same way that “killing the American he-devils” might make me think twice about Jihadist Islam or stockpiling weapons to prepare for Armageddon makes the Branch Davidians seem not quite aligned.

But I cling to “by their fruits ye shall know them,” and I keep reminding myself that it is a very large elephant and I am a grasping blind woman. The shelf of “Bibles” that make me feel aligned is large and eclectic. The very fact of Thomas Merton and the Dalai Lama makes me feel God. The art of Sher Fick makes me feel God. The novels of Haven Kimmel make me feel God. The poetry of Elizabeth Bishop makes me feel God.

I am completely open to being told I am wrong about all this. Therefore, I would welcome a discussion here. Feel free to agree, disagree and/or throw in some new ideas of your own.

Hinds’ Feet on High Places

I just finished my annual re-read of Hannah Hurnard’s Hinds’ Feet on High Places. I first encountered this book when my sister was in college and I was still in high school, and the first time I read it I was working at a camp in the middle of the Adirondack Mountains. The copy I own is the 1977 edition; I bought it from Amazon Used to make sure I got the edition that I originally read.

Anyone who knows me well would be very surprised to hear how much I love this book and that I have probably read it at least 20 times.My love for this book is surprising even to me because I often do not like “Christian fiction”: I finally broke down and bought The Shack in the name of cultural literacy and had to force myself through it. Actually, I skimmed most of the second half, muttering “Yeah, yeah, yeah” as I flipped through the last fifty pages.

I know that my literary tastes expose me as a bit of a Cecil Vyse in A Room With a View. As Lucy explains after he walks out on Freddy singing: “It’s ugly things that upset him. He’s not uncivil to people.” Her mother replies, “Is it a thing or a person when Freddy sings?” I find myself in this bind when reacting to some spiritual novels, and I don’t like myself very much. I am sure all of these writers are much better people than I am, and I admire that. I just don’t like the writing. Much of it feels like eating a Twinkie when what I want is wheat bread.

And Hinds’ Feet on High Places is wheat bread for me, and I read it every June as I get ready for summer vacation. It is a completely unapologetic allegory, in the tradition of Everyman. Each character is named after a trait: Much Afraid, Craven Fear, Resentment, Suffering, and therefore the book is more like an icon than like a badly written novel sneaking spirituality in the back door. It reminds me of The Ladder of Divine Ascent. This is a painting I heard of in another of my re-reads: In the Spirit of Happiness by the Monks of New Skete, a Russian Orthodox Monastery near Albany. They are the same monks who raise German Shepherds and write the dog obedience books. The icon shows a group of monks ascending toward Christ while devils shoot arrows at them on the right and a group of angels cheers them on at left.

And Hinds’ Feet on High Places is wheat bread for me, and I read it every June as I get ready for summer vacation. It is a completely unapologetic allegory, in the tradition of Everyman. Each character is named after a trait: Much Afraid, Craven Fear, Resentment, Suffering, and therefore the book is more like an icon than like a badly written novel sneaking spirituality in the back door. It reminds me of The Ladder of Divine Ascent. This is a painting I heard of in another of my re-reads: In the Spirit of Happiness by the Monks of New Skete, a Russian Orthodox Monastery near Albany. They are the same monks who raise German Shepherds and write the dog obedience books. The icon shows a group of monks ascending toward Christ while devils shoot arrows at them on the right and a group of angels cheers them on at left.

Hinds’ Feet on High Places is similarly and unapologetically allegorical. The premise of the book is that Much Afraid, a young crippled shepherdess in the employ of the Shepherd, asks to be taken to the High Places away from her Fearing relatives, where “perfect love casteth out all fear.” The Shepherd is overjoyed to grant this request, has been waiting for Much Afraid to ask, and gives her as her companions on the journey Sorrow and Suffering to help her up the mountain.

Here I stop and say “Thank you, sir. May I have another” because I need this God Smack. Asking to walk a spiritually evolutionary pathway is not buying an airline ticket to Jamaica. It is taking off your shoes and heading over the hot coals. We are “too, too solid flesh” and the only way to get it in shape is through training, which is another reason I love this book: it reminds me of the summer of 1988 when I backpacked through Europe alone. I lived on $20 a day, filling my pockets with bread and cheese at the Youth Hostels and hiking everywhere. My trip included a week in a tiny hostel in the Austrian Alps, far enough up that I could hike up to the snowline. By the end of the summer, I was a Lean Mean Hiking Machine and also quite able to handle myself in just about any strange circumstance.

The allegory is both so true and so overt that it allows complete entrance of the individual reader into the tale. Nothing blocks the reader from inserting the self: no silly plot devices or clever new metaphors that distract. Just a nearly skeletal rendering of the indeed harsh reality of the spiritual journey. Very few butterflies and rainbows but plenty of drear landscapes and difficult delays.

As Much Afraid makes her journey, here are the places she must traverse:

Detour Through the Desert, symbolizing long and difficult periods of bleakness and hardening to difficulty

On the Shores of Loneliness, symbolizing long periods of aloneless and solitude

Great Precipice Injury, symbolizing the truly treacherous task of attempting holiness

The Forests of Danger and Tribulation, symbolizing the hardships that will intensify once you get closer

The Mist, symbolizing periods of confusion and tedium

The Valley of Loss, symbolizing the seeming destruction of all that has been gained

The Place of Anointing, symbolizing the times of peace allowing preparation for great tragedy

Grave on the Mountains, symbolizing the requirement to give up all you had hoped for

Healing Streams, symbolizing the grace that comes after complete surrender of personal will

High Places, symbolizing the freedom and clarity of spiritual life beyond personal dreams

This book knocks me flat every time I read it. It is the astringent reminder of just how difficult a task it is to set oneself on the spiritual path. Along the way, Much Afraid’s enemies attack her repeatedly: Self-Pity, Resentment, Bitterness, they all make an appearance and try to divert Much Afraid from her goal. I have been there, and these vile enemies, which of course come from within, do try their darnedest to halt my progress.

I re-read this book every year as an assessment: Which of these places have I recently traversed? How did I handle it? Where am I on this journey? Which of these enemies am I listening to?

This year, with all the knowledge about Asperger’s I have gained in the past twelve months, one scene jumped out at me in starker contrast than in my previous readings. Much Afraid is told she is very close to her goal and is directed to go alone to a rocky crag where a silent preist stands at a grim altar. The Shepherd tells her, “Take the natural longing for human love which you found already growing in your heart when I planted my own love there and go up into the mountains to the place that I shall show you. Offer it there as a Burnt Offering unto me.”

Much Afraid, knowing that she hears aright, proceeds. She accepts that 1) she may have been deceived by the Shepherd all along 2) she is giving up her heart’s desire 3) her enemies might be right that she will be abandoned on “some cross” 4) she will do it anyway because she wants the Shepherd more than the promises. Fearing she cannot do it, she asks the preist there to do it for her and also asks him to bind her in case she struggles to prevent it.

When Part One ends, she has suffered her all, given her all, and accepts that “It is finished.” This part is so important and struck me so this time through. I can trace my own path through every one of those parts of the journey: suffering, loneliness, injury, confusion, danger. But I am not sure that I have made this final sacrifice.

When Part One ends, she has suffered her all, given her all, and accepts that “It is finished.” This part is so important and struck me so this time through. I can trace my own path through every one of those parts of the journey: suffering, loneliness, injury, confusion, danger. But I am not sure that I have made this final sacrifice.

Many of the Asperger’s books say that the hardest part for a spouse is to accept that you might never get the kind of love and empathy one would wish from a partner. Many women cannot accept this and leave to find it elsewhere. Other women take the gifts that are offered and find that empathy elsewhere, in friends or family.

Perhaps this is Summer 2009’s leg of the journey. I know I am not leaving, and I know I am currently seeking empathy and love in other places such as friends. But I also know that I have not yet really made that sacrifice and it lies before me.

For all she knows, Much Afraid has accepted her own death on that altar. And yet when she awakes after three days, she bathes in Healing Streams, is healed of all deformity and disfigurement, and is finally able to leap like a deer. She is turned into Grace and Glory, and her companions Sorrow and Suffering become Joy and Peace. These are the promises of the High Places, and yet here’s the rub: they lie the other side of that grim grave.

I know I’m not there yet. I know I’m closer to it. I know I fear it. Tough as I appear, I don’t like pain. I know that this event will be unseen, unknown, because it will happen inside.

The other annual event linked with this book is my climbing Bald Peak, which is in the Berkshires, an hour’s hike from the Bartlett Camp. I go there to steel myself and to physicalize the truths of this book and of every great spiritual tradition I have ever encountered. I also steel myself by listening to this beautiful album: Doug Howell’s settings of the poems from the book, which are all from The Song of Solomon.

Maybe this is the summer I finally get beyond the reach of Resentment and Bitterness and Self-Pity by ripping that human-love plant out, but maybe it’s not yet ready to be uprooted. In the meantime I will at least once again set my foot on the path, because the invitation is always there.

Mid-life Crisis

We interrupt my regularly scheduled intellectual spouting to bring you my mid-life crisis.

First there was this: I snatched The Red Convertible off the new books display at the library because I love Louise Erdrich. I read the inside front cover, I skimmed the table of contents, I flipped to the inside back cover.

I said, What the heck! That’s not Louise Erdrich. Louise Erdrich is young and dewy!

I said, What the heck! That’s not Louise Erdrich. Louise Erdrich is young and dewy!

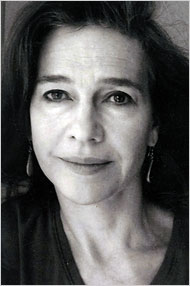

But, apparently not any more. That → is the Louise Erdrich who wrote The Blue Jay’s Dance.

And that ← is the Louise Erdrich who just published The Red Convertible and who dealt with Michael Dorris’ suicide and many children.

Then there was this. Remember Kelly McGillis?

Yes, I mean THIS ↓ Kelly McGillis from Top Gun. Or even THIS ↓ Kelly McGillis from Witness.

Now she is THIS ↓ Kelly McGillis

And remember Meggie Cleary of The Thorn Birds television special? I wanted to be Rachel Ward. She was so beautiful she corrupted a PRIEST. Or I most definitely would have been Rachel Ward in Against All Odds. I remember getting THIS ↓ haircut and buying an orange bathing suit in order to embody Rachel Ward in this movie. I had no interest in Beau Bridges, just wanted to look like Rachel Ward. Well, now she looks like this↓.

Then there is Kathleen Turner. Remember her in Body Heat?

Here she is today in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

Which is all to make me feel better about this↓:

We are most definitely NOT going to talk about THIS↓:

Though I would be very glad to talk about THIS↓:

Know what I mean?

Down the Up Staircase

For many years after we moved to our farm in rural upstate New York, I had a recurrent nightmare that I had not really graduated from Amherst College. In the dream I would be my waking age of 24, eventually 30 and later still 37, and yet I would have to return to Amherst for three more semesters, leaving my husband and child – then later two and three children – back at home. In most cases the dream began mid-semester, and I was very behind in my Religion course, owing a paper I had not yet started, nor had I even attended the class, leaving me unable to even start it.

This dream, needless to say, bothered me quite a bit, so much so that I dug out my Amherst diploma and my Phi Beta Kappa key and placed them prominently above my desk to remind me that I really HAD graduated. I also hung my Master’s diploma and my permanent high-school teaching license. But this did nothing to stop the dreams, which continued to recur once a month or so.

I am sure my mother and father, watching me receive my Amherst diploma in 1990 and then leave Massachusetts with my fiancé to buy a farm in Central New York, must also have wondered if I had really graduated. Or if I had, with a degree in what? Tractor Operation?

My father had grown up in Western New York, youngest child of second-generation Irish immigrants on both sides, on a small farm, hating it. He hated killing chickens and he hated milking the cow and he hated the No Irish Need Apply stories he had heard, and so he embraced America – the jazz and the City, and he dreamed of nights in a Harlem club, ringed in cigarette smoke, writing. Thanks to the GI Bill, he had just matriculated at Columbia’s Journalism school when his father’s death put an end to his dreams. He instead attended nearby Canisius College, studied accounting, cared for his widowed mother, landed a post in the GM executive building, and married the sparkling platinum blonde at the water cooler.

My father had grown up in Western New York, youngest child of second-generation Irish immigrants on both sides, on a small farm, hating it. He hated killing chickens and he hated milking the cow and he hated the No Irish Need Apply stories he had heard, and so he embraced America – the jazz and the City, and he dreamed of nights in a Harlem club, ringed in cigarette smoke, writing. Thanks to the GI Bill, he had just matriculated at Columbia’s Journalism school when his father’s death put an end to his dreams. He instead attended nearby Canisius College, studied accounting, cared for his widowed mother, landed a post in the GM executive building, and married the sparkling platinum blonde at the water cooler.

Meanwhile, my mother had also moved up in the world, from the ten-year-old whose mother (my grandmother) had snatched her and her brothers from beatings by her alcoholic father and evictions from apartment after apartment and had found respect caring for the children of the well-to-do, and my mother grew to become a popular high-school socialite. Later, with her high-school secretarial diploma in hand, she spent two years working at the Vatican and then returned to Western New York, the world-traveler and eye-catcher in the secretarial pool at the radiator plant.

Helped by America’s post-World-War-II prosperity and GM’s solid position in the Big Three, my parents managed to gain a firm toe-hold in the middle class, with a house and car and three healthy children. Even so, my mother always feared her own exposure as the sole non-college-graduate at Mothers Club, and my father’s unspoken dreams and unwritten books eddied around our feet like discontented waves in that house on Harrison Avenue.

We three children all felt it and sought to climb beyond the middle-class staircase landing, especially when our academic shining also served to blind others to the dark issues muddying the dull glow of the existence my parents had hacked out of their respective pasts. The Irish genes carried intelligence as well, and my siblings and I had a clear and unobstructed path to most any college we chose and beyond. My sister eventually earned a PhD and a prestigious educational consulting job, and my brother added an MBA to his engineering degree to move far above my dad in the GM hierarchy. By the mid-80s we all three were riding the up escalator of the rising middle-class.

In 1985 I was catapulted from my GM hometown into Central Massachusetts to land among the nation’s elite at Amherst. A veritable conspiracy of forces had propelled me there. In 1980 The Official Preppy Handbook hit my junior high school like contraband. We Italian and Irish immigrants’ children, still virtually loam-footed from digging the Erie Canal, pored over this book like a National Geographic full of naked bushmen, as stunned and confused by what we saw as by Papua New Guinea’s painted tribes.

In 1985 I was catapulted from my GM hometown into Central Massachusetts to land among the nation’s elite at Amherst. A veritable conspiracy of forces had propelled me there. In 1980 The Official Preppy Handbook hit my junior high school like contraband. We Italian and Irish immigrants’ children, still virtually loam-footed from digging the Erie Canal, pored over this book like a National Geographic full of naked bushmen, as stunned and confused by what we saw as by Papua New Guinea’s painted tribes.

Oddly enough, my best friend that year was suddenly plucked out of our canal town by the remarriage of her divorced mother to a movie magnate in DC. Her new life bestowed upon her a stone mansion in Georgetown and attendance at a prestigious all-girls prep school. She was the real thing, not the pseudo-preps my friends and I were at Lockport Senior High School in our K-Mart Oxford cloth shirts and Dickies.

The three prongs of that mighty trident – parental dreams, best-pal jealousy, and my own intellectual inheritance – prodded me to apply to the Little Ivies, and the Amherst acceptance clinched it by topping 1983’s US New and World Report listing of Top Liberal Arts Schools. The world was my oyster, and I was invited to sit smack in the middle of that pink cushiony mollusk.

However, something happened once I got there. Very few people are able to analyze their own historical context clearly, much less a young woman way out of her league among peers who were comfortably inheriting positions at the top of the heap. I was so stimulated by the rarefied intellectual atmosphere that I did not recognize the signs of decadence and over-consumption that were sweeping the national economic landscape and intensifying my culture shock.

Once the novelty of it all wore off, some underlying sense of unease set in. I am sure I stuck out like a sore thumb at Amherst; after all, it was not hard for me to pick out the other scholarship/work-study students. I remember my shame at how easily my name was forgotten or never learned by my wealthier classmates. I remember one in particular who wore his Exeter legacy like his own skin and another who co-opted our student art exhibition into her own personal soiree. I was shocked by this, though moral indignation took a back seat to intimidation and insecurity.

Nevertheless, by the time I met, fell in love with, and accepted the marriage proposal of a UMass Ag School graduate in my junior year, I was quite happy to turn around on the lingerie floor and take the down escalator past my parents and even further down, to our economy’s basement: farming. It is true I had fallen in love with an Ag major, and it is true that he was also a borderline Marxist, but it is also true that the chance to buy a farm and work very hard at manual labor struck a deep and resonant chord already vibrating within me, where law school or marrying a future Wall Street executive did not.

It wasn’t until years later, when I ran into Dr. Ruby Payne’s 1998 Framework for Understanding Poverty, that my subconscious collegiate reasoning was clarified. In the public education world, Dr. Payne’s theory is used to explain why it is so difficult to help students rise out of generational poverty. Personally, I was not so much struck by the “hidden rules” of the lower class (which engulfed me both in rural Central New York and my hometown) as I was by articulation of the hidden rules of the upper class, which I had divined in college but not previously seen articulated so clearly. This very prize had been right there, tantalizingly just inches beyond my fingers, and I could have quite easily ridden that late-Reagan/early Clinton wave right into fortune and luxury, but I did not. There was something in that glittering mirage that turned my stomach, that made me turn around, that made me run down that up staircase as fast and as far as I could.

It wasn’t until years later, when I ran into Dr. Ruby Payne’s 1998 Framework for Understanding Poverty, that my subconscious collegiate reasoning was clarified. In the public education world, Dr. Payne’s theory is used to explain why it is so difficult to help students rise out of generational poverty. Personally, I was not so much struck by the “hidden rules” of the lower class (which engulfed me both in rural Central New York and my hometown) as I was by articulation of the hidden rules of the upper class, which I had divined in college but not previously seen articulated so clearly. This very prize had been right there, tantalizingly just inches beyond my fingers, and I could have quite easily ridden that late-Reagan/early Clinton wave right into fortune and luxury, but I did not. There was something in that glittering mirage that turned my stomach, that made me turn around, that made me run down that up staircase as fast and as far as I could.

Dr. Payne differentiates among the three sets of “rules” followed by the generational poor, the middle-class, and the wealthy with regard to seven different value sets. In terms of possessions, the poor focus on relationships, the middle-class on material items, and the wealthy on one-of-a-kind objects, legacies, and pedigrees. With food, “having enough” is the hidden rule for those in generational poverty, “quality” is important to the middle class, while the wealthy focus on “aesthetic presentation.” Regarding fighting, the poor resort to physical means, the middle-class to discussion, and the wealthy to social exclusion and lawyers. The poor focus on present time, the middle-class to planning for the future, and the wealthy to preserving past history and traditions. While the poor base their acceptance of others on liking, and the middle class judges a person’s achievements and success, the wealthy consider connections and social standing.

Of course these are generalizations and the many exceptions mock any indication of this theory’s irrefutability, but reflecting back on my Amherst days, this theory resonated with my own take on the unspoken social forces that caused me considerable unease in college, even granting the excesses of the era. I saw and heard and experienced these rules that guide the wealthy, and I turned and walked away from them. Social exclusion, preservation of tradition and legacies at the expense of justice, social standing as more important than people – these were not values I was raised with, and they were not values I aspired to adopt.

My husband and I chose instead one of the hardest rows to hoe, literally, and have sacrificed literal blood, sweat, and tears to dig our way out of the debt required to buy, equip, and stock a dairy farm. And yes, I felt foolish sometimes, and yes, that subconscious need to return and “finish” my Amherst degree seemed to indicate my doubt that I was right to turn and descend, my underlying sense that I had missed something that Amherst could have taught me about success and comfort and the easier life. Perhaps I just needed a few more semesters to get used to the idea.

The current economic downturn, however, has turned this all on its head. Even the middle-class status my family fought to attain appears to be crumbling. My older brother, whose GM division was sold to Delphi, just lost the retirement health insurance he had worked 40 years to earn. My mother’s generous widow’s pension is in question as GM itself has just teetered into bankruptcy. Many of my fellow 80s grads moved to the Bright Lights, Big City and became Less Than Zero, and the Wall-Street-bound might very well now be without work. Furthermore, the wider world, through the basics of supply and demand – is stealing away, at lower-but-welcomed wages, the very jobs that formerly bought us our large houses and multiple cars and weight problems.

I heard recently that in 2006, the average income of the country’s 400 wealthiest people was $263 million – each. Had it been $263 million total, that would still have been over $657,000 each – surely more than enough. But no, it was $263 million each. This meant that the wealthiest 1% of the population took home 22% of the national income. Picture a room in which there are 100 loaves of bread. One hundred people enter the room and ONE person takes 22 of the loaves for himself, leaving the other 99 hungry to split up the remaining 78 loaves. One person gets 22 loaves; the others each get less than four-fifths of one loaf. That’s the number 22 compared to .78. Would anyone want to admit to being that person? I would not, especially if this amassing of wealth was in the name of “preservation of tradition” to allow for “aesthetic presentation” and “social standing” won through “social exclusion and lawyers.” Hello, my name is Mephistopheles.

Now that two decades of economic growth and over-consumption are coming to a screeching halt, I would love to credit myself with prescience, but I think it was something more like a good grasp of reality. In the environmental world, exponential growth is simply not possible. A species’ population will grow until it exceeds the ecosystem’s carrying capacity, at which point it will drop off. A parasite will thrive only until its host sickens unto death. Even in the nursery school playroom, the other children will ignore the child who takes two toys, but when that same child takes ten toys, the scene devolves into Lord of the Flies.

Now that two decades of economic growth and over-consumption are coming to a screeching halt, I would love to credit myself with prescience, but I think it was something more like a good grasp of reality. In the environmental world, exponential growth is simply not possible. A species’ population will grow until it exceeds the ecosystem’s carrying capacity, at which point it will drop off. A parasite will thrive only until its host sickens unto death. Even in the nursery school playroom, the other children will ignore the child who takes two toys, but when that same child takes ten toys, the scene devolves into Lord of the Flies.

I would sneer with an “I-told-you-so” smirk were it not for the faces of my own three children. Despite my climbing down economically to live on a farm, I still find myself imaging my own progeny at Harvard and Yale – the next step beyond my own college achievements. However, now that my eldest is thinking about college, I am fearing that schools like Amherst might be nothing but a dream. Like many parents in these economic times, I can only foresee for my kids a lower standard of living than my generation’s. I was expected to go one better than my parents, but there is the very real possibility that our kids will have to go one or two worse. Shrinking endowments, limited post-graduation job opportunities, a big non-American world now demanding its fair share. I suppose what’s coming is exactly what I felt was justified twenty years ago: a more equitable division of the world’s resources. But I find myself cringing at that how that will affect my own three babies.

The most dire and Apocalyptic predictions have us all holed up in bunkers, defending ourselves from rampant flu viruses or terrorists and happy merely for enough to eat. If that is coming, I suppose my husband and I made the wisest choice possible. At least after Armageddon we’ll still have plenty of milk and beef. I keep imagining those I love all ending up here with us, as jobs and economies continue to fall.

Rather than peddling credit default swaps or sub-prime mortgages, we joined the low-paid ranks of those .5% who provide the other 99.5% with their low-priced foodstuffs. I would never suggest that farming is easy: far from it. It takes everything my husband and I have and know to keep this enterprise afloat. Agriculture is a desperately competitive business, not because marketing experts are outmaneuvering each other to sell the “better” product but because high input costs and low prices for product make economic survival near impossible. It takes a profound knowledge of biochemistry, agricultural economics, management strategy, and a vast array of technical and mechanical skills to keep this dairy ship afloat. But we do it because it seems right.

Many a day it also takes an infusion of philosophy to keep us in it. When life seems so much easier in another place, it takes the ideas of Marx and Thoreau and Merton and Willa Cather and Shakespeare and Elizabeth Bishop and Gaston Bachelard for us to carry on. And for this I am extraordinarily grateful to my Amherst years for giving me these.

My Dad was a veritable Hoover of ideas , just a great quiet curiosity vacuum for information and news and thoughts, and I still own the 40-volume Harvard Classics set my father bought in 1938. I also have his college copy of Readings for a Liberal Education. They sit in my study on the bookshelf he purchased to hold them, a bookshelf that sat in his own farmhouse way back. I also know that in his eyes they are not a rebuke of the choice I made to receive the pearl of great value, bought with all my parents had, and to bring it back to the country and hurl it before bovine; the presence of these texts is neither ironic nor anomalous here in my farmhouse in rural New York. They are, instead, the ultimate integration of all my father held dear. Because I think, really, that this is what he wanted and what he wanted for me: a life of the mind. Not the trappings, not the belief that I deserved more, that the well-educated deserve their 2200%, but rather that the profound and lyrical ideas of the world’s great thinkers are themselves the pearl of great worth.

And in that regard I did continue upward; that is the true height to which I have climbed. I have not used my knowledge to hoard more than my due; I use it to provide food to others – many others. My Amherst legacy is in the vast network of connections I am able to see, the literature to which I have been exposed and continue to seek, and the knowledge and analysis skills I pass on to my children.

Several years ago I stopped having that recurring Amherst dream. Perhaps it was turning forty. Perhaps it was hearing tales of the bubble bursting. I guess in middle age I have found peace with the choices I made twenty years ago. My mother has also, and I am sure my father, were he still alive, would affirm that I have attained that dream he had back on his own family’s farm.

I made a choice to grasp the brass ring of knowledge and bring it back down to the humus, the very root of existence, of humanity, and of humility. I can only hope that if we as a country are forced by world-wide inevitabilities to all do the same, that the wisdom we sought in order to attain our great wealth is enough to sustain us even without the financial rewards.

Feel free to join my rant in a comment or rant at me.

Writing by the ocean, under a tent, summer

This post is for my friend Kevin, an extremely good poet who should have his own blog because I forget to look at Facebook.

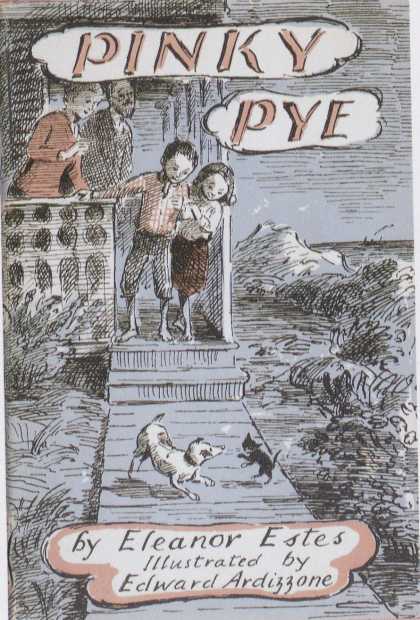

No cars were allowed on the island, nothing on wheels in fact, except bicycles and small boys’ express wagons…. Just as there were no vehicles, so there were no streets either. There were very narrow boardwalks instead, and people had to walk single file.

A short way ahead, on a slight rise so that it was a little higher than the others, Rachel could see a perfect little brown-shingled, weather-beaten cottage. It looked like a doll house. Many of the houses were like rectangular boxes. But this one had corners and elbows to it as though a room or a porch had been added here or there as an afterthought. Very pale pink roses spread sparsely over the tiny porch roof.

Stepping inside, almost expecting to discover the three bears in a little house like this, they found, not bears, but other surprises – little alcoves, built-in tables on which to work or eat or study or play, and one was set for supper.

During the afternoon Papa worked very hard putting up a huge green umbrella he had bought from the Army and Navy store. It was oblong in shape, more like a roof than an umbrella, and strong ropes on all four corners tied to staves in the ground held it securely down. Papa had put it up on the ocean side of The Eyrie, and it was spacious enough for all the family and even some guests to sit under on a hot day and look out over the wide Atlantic.

Papa eased himself into his chair under the big green umbrella and, with injured foot resting on a stool and with a small table that fitted nicely over his lap for his typewriter … he put a piece of blank paper in the typewriter. He was accustomed to work, and just because he had a lame foot, he was not going to bask under the green umbrella and do nothing.

Papa eased himself into his chair under the big green umbrella and, with injured foot resting on a stool and with a small table that fitted nicely over his lap for his typewriter … he put a piece of blank paper in the typewriter. He was accustomed to work, and just because he had a lame foot, he was not going to bask under the green umbrella and do nothing.

In the cottage everyone was happy to hear the sounds of the typewriter, for it meant that, since Papa was at work, he was happy. Today, as on many other occasions, Papa preferred to stay at home, and with his typewriter on his lap, and Pinky [the kitten], too, he would work, think, study, dream.

While the family was away at the beach, picnicking, picking up shells, what was being typed under the green umbrella by the typing team of Pinky Pye and Papa?

CAT GAMES

Dear cats: Following are some simple games called Solitaire.

Game of Take Your Time Game of Pencil Grab Game of Pencil Hide Game of Mouse Game of Making Beds Newspaper Game Game of In and Out the Bureau Drawers Game of Half-Dead Mouse Game of Closet Creeps Game of Dog’s Ears Game of Fix the Eye Game of Catch the Fly Game of Faucet Drip Game of Pretend Mouse Game of Knock It Over Game of Woe-Be-Gone Bird

Uncle Bennie and Rachel were the first to arrive, hot, panting, and thirsty. Papa was still sitting under the green umbrella, typewriter table, typewriter, and Pinky all still on his lap. He was looking blandly and vacantly out toward sea. There was a lot of typing on the page. And all rather badly typed.

Pinky Pye is an annual re-read event for me once summer is under way. Does anybody else have season-starter re-reads? And, have a Fabulous Fourth!

Anniversary? Perenniaversary?

I was reminded that this Tuesday just past was our anniversary at 6 PM that night when I got a beautiful e-mail from my sister. I chuckled a bit when Andy came in at 6:30 PM, and I said to him, “Hey, it’s our anniversary.” He chuckled, too, and said, “Oh, yeah. It is, isn’t it.”

Zeke the Hound wants to give me away

Kath, me, Andy, David; Dress made by Kathleen McCarthy, sister and anam cara

Part of the reason we are both kind of blasé about June 30 as any kind of significant date is because we had already bought the farm and been living on it for six months by the time we wed. In our own minds, we had already been married half a year.

Also, of all the moments that seem important in our marriage, that particular hour on that particular day in 1990 seems like a live coal in the sea. That was the easy part. It’s the 6,935 days since then that have been the “marriage.”

However, we also decided, Andy and I, that our cavalier attitude about our wedding day is perhaps not quite healthy. We probably should at least REMEMBER the day we wed.

Part of what makes me uneasy about celebrating THAT DAY as so important is that it somehow trivializes all the others since, like saying, “Gosh, THAT day of fun and ceremony and family and laughter, THAT day was awesome, and everything since doesn’t really measure up.”

Latin geek that I am, I just love teaching the Latin root “ann/enn” to my students – so many cool words come from it: millennium, annuity, biennial, bicentennial, superannuated, and of course anniversary, literally “the turning of the year.” It is how I keep straight annual flowers from perennials. Annuals last for “one year” while perennials (adding the prefix “per,” meaning “through”) last “through the years.”

Perhaps this is why I dislike the word “anniversary.” As I am likely to mutter sarcastically in the greeting card aisle, “Whew! Just barely made it ONE MORE YEAR so we can remember that joyous wedding day again!” At this point the owner of the store calls security and says “Would you get that damn Latin major OUT of here!”

So, for all you Latin lovers out there, may I suggest a new name for anniversary? How about perenniaversary, to celebrate making it “through” one more year and still going?

This is most likely just a pet peeve particular to my unique and annoying mix of etymology addiction and Asperger’s survival. So take it as such. If you like it, feel free to adopt it.

Meanwhile, at least my beloved sister gets it and sends appropriate sentiments. She said:

Turn the page.

Turn the page.

Write your names together once more.

Dance a bit on the porch.

Smell the dark sweet night air.

Sleep beside one another.

It is enough.

She also sent this poem, which is lovely:

The Book

by Fred Andrele

Photo Mary Warren Bonafini, fabulous sister-in-law

Did I meet you in that little shop

where the book of love is kept behind the counter?

Impossible, except our names are there

in golden script upon the luminary page.

Who would have thought the string bean boy,

the girl who squats and hops like garden toads

would find each other in the deep immensity

but there you are, my fingers trace your name.

I see mine linked with yours by radiant hearts

the shop’s proprietor, his quiet smile,

before the book is closed, takes up the feather pen

turns the page, and writes our names again.