Guest Movie Maker Elliot Bartlett

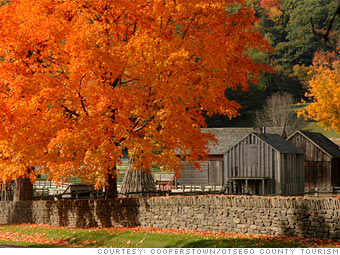

My brain has been so swamped with living my life that I have had no creativity left over for blogging. Hopefully, it will come back after this heat wave passes. In the meantime, luckily, my son Elliot has stepped in and allowed me to post his first movie. His beloved aunt challenged him to take the Bing Crosby version of “Dear Hearts and Gentle People” and create a video of Norwich, NY, our nearest “town,” which truly is one of those quintessential small towns. The story goes that Norwich was only allowed to incorporate as a “city” if it had a certain number of streets, so there are several streets that have different names on either side of an intersection. You will be driving along Borden Avenue, cross through an intersection, and suddenly be on Fair Street. Clever, those founding fathers!

Yes, although the boy is 12, this is very intentionally tongue-in-cheek. Elliot has a very sophisticated level of textual analysis and presentation. He recently read The Catcher in the Rye and noted that because the pace of the narrative was so much slower than the middle grade books he normally read, that Salinger was able to go more in depth about Holden’s thoughts and feelings and he liked this style, was planning to read more adult books. He’s twelve. Here’s the video.

And here is the young movie master. Be watching for him in years to come.

Couldn’t resist adding this one too:

Happy Confluence of Winter Books

It is 10 below zero here today, and I just finished the perfect book to read when it is this cold. It also occasioned one of those happy confluences when a favorite children’s book suddenly appears in adult form and is equally good. I have probably read Winter Cottage by Carol Ryrie Brink 30 or more times. Of course I had discovered Caddie Woodlawn and Magical Melons and then Two Are Better Than One and Louly by third grade, but then when I discovered Winter Cottage, something about it made it my favorite of her books.

It is 10 below zero here today, and I just finished the perfect book to read when it is this cold. It also occasioned one of those happy confluences when a favorite children’s book suddenly appears in adult form and is equally good. I have probably read Winter Cottage by Carol Ryrie Brink 30 or more times. Of course I had discovered Caddie Woodlawn and Magical Melons and then Two Are Better Than One and Louly by third grade, but then when I discovered Winter Cottage, something about it made it my favorite of her books.

I finally had a name for the reason after I read The Poetics of Space in college, and recognized what Gaston Bachelard called “intimate immensity” or the sheltered, small, hidden space that allows the spirit to roam freely. Bachelard’s contention is that such phenomena are ontological and that we experience them when a writer is able to express them for us. I experienced intimate immensity when I read Winter Cottage.

I finally had a name for the reason after I read The Poetics of Space in college, and recognized what Gaston Bachelard called “intimate immensity” or the sheltered, small, hidden space that allows the spirit to roam freely. Bachelard’s contention is that such phenomena are ontological and that we experience them when a writer is able to express them for us. I experienced intimate immensity when I read Winter Cottage.

The protagonist is Araminta Sparks, called Minty, who is on her way to Chicago with her sister Eglantine (Eggs) and their father Pops. It is the midst of the Depression, and their car breaks down on a back road they have accidentally turned onto. They find a summer cottage on a lake and “break in” to spend the night. Because they are hauling all the canned goods from Mr. Sparks’ failed grocery store, they eventually decide to winter there, planning to leave “rent” for the landlords whom they do not know.

Moving on to North of Hope. I had discovered the Loyola Classics series in Fall of 2008, and after I bought and read In This House of Brede, I made it known that I would like several more from the series. My lovely husband bought me three for Christmas last year, including North of Hope because Andy knows I like books about hardship, cold, Native Americans, and Catholics. Besides, look at that cover. Is that not lovely?

When the weather turns cold and nasty here, I usually pull out The Shipping News or Alistair MacLeod’s Island to make me count my blessings, but this year I picked up North of Hope. (I would also suggest Peace Like a River in this grouping). Jon Hassler is new to me, but I am now going to run out and read more of his books. He was a high-school English teacher and then taught college, later becoming Writer in Residence at Saint John’s University in Minnesota.

When the weather turns cold and nasty here, I usually pull out The Shipping News or Alistair MacLeod’s Island to make me count my blessings, but this year I picked up North of Hope. (I would also suggest Peace Like a River in this grouping). Jon Hassler is new to me, but I am now going to run out and read more of his books. He was a high-school English teacher and then taught college, later becoming Writer in Residence at Saint John’s University in Minnesota.

North of Hope focuses on Father Frank Healy, a priest having a crisis of not so much faith, as hope. He returns to his hometown parish to sort this through and is reunited with his best friend/almost girlfriend from high school Libby, who, though not religious, is similarly facing a crisis of hope as she deals with her manic-depressive daughter, drug-dealing doctor husband, and her own rekindled passion for Frank. These two spend a winter supporting each other through some true tragedies, and find in each other’s Platonic love and support, the means to find hope once again.

Reading Winter Cottage on a cold day is like drinking hot cocoa with marshmallows. Reading North of Hope was like drinking very strong espresso with maybe a shot of whiskey: adult, realistic, true, bitter, and yet still warming. The epistle from this morning’s Mass readings was from First Corinthians: “When I was a child, I used to talk as a child, think as a child, reason as a child; when I became a woman, I put aside childish things.” As a woman I have not totally put aside childish things; I still read the Little House books and I still read Winter Cottage. As a child, these books were an escape into another world, a rural, character-building place I wanted to be. And when I reread these books now, they do rekindle that romantic, adventurous feeling that inspired me as a girl.

But now I LIVE in that world, where things are rural and character-building, and I cherish the tales of adults facing these hardships with courage and integrity. Frank Healy is my grown-up Minty Sparks. The other time I had a similar book confluence was when I discovered Willa Cather’s Prairie Novels and had found the adult equivalent of Laura Ingalls Wilder. Alexandra Bergson is now my role model as much as ten-year-old Laura was.

In addition to the tough weather-beaten and life-beaten heroes I sought, I was also looking for books that created that “intimate immensity” of a small, warm, protected place in the midst of the snow and the chaos and the hardship. I think even as a kid I kind of knew that life could be a tough journey, and I girded my loins by finding heroines who took it on bare-handed and adult characters who provided safety and warmth. There is Pops at left, making his famous pancakes. That kitchen is warm, and light, and smells good. At right is Pops playing chess by the fire. It’s cold outside, and Minty’s mom is dead, and they have no home or money, and yet they have made a place of safety.

In addition to the tough weather-beaten and life-beaten heroes I sought, I was also looking for books that created that “intimate immensity” of a small, warm, protected place in the midst of the snow and the chaos and the hardship. I think even as a kid I kind of knew that life could be a tough journey, and I girded my loins by finding heroines who took it on bare-handed and adult characters who provided safety and warmth. There is Pops at left, making his famous pancakes. That kitchen is warm, and light, and smells good. At right is Pops playing chess by the fire. It’s cold outside, and Minty’s mom is dead, and they have no home or money, and yet they have made a place of safety.

In North of Hope that place of safety and warmth is much more abstract, in the way that adult things are. One character dies when his car goes through the ice, another is hospitalized in a mental clinic, another comes close to throwing herself in front of a train. There are no places of comfort for many of these characters. Frank has to find that place inside himself, as do the other troubled characters in the book. Most of them feel North of Hope itself, and hope IS that warm place by the fire. The hard thing in adulthood is creating that Winter Cottage metaphorically. And within.

Winter in Central New York

My oldest son created this one day when he was bored. I think it’s brilliant. He made it about four years ago, thus the spelling errors.

It’s even funnier to those of us who live here because we can name most of the people in the vehicles that go by. In the white station wagon is the wife of the guy who fixes our cars. She is on her way into Norwich to buy car parts for her husband. They live in a strange enclave in the woods, built into a hill so that half is underground. We call it The Bunker. For the first many years we dealt with him, we were instructed to leave our car up on the road with the keys in it – not to drive down into the property. For a long time we suspected he was in the witness protection program, but now we just suspect they are older hippies. We also suspect they might be practicing nudists because sometimes we’ll stop at the house to pay our bill, and they have obviously just thrown on robes. Great mechanic. Cheap prices. Life in backwoods New York.

The truck that pulls in the driveway is our trucker Sue who takes our old cows to auction when they need to go. Sad but true. By some fluke of the camera, the film slows her down and then speeds her up. I laugh every time I watch it.

The other smaller car that pulls in is the artificial insemination guy. If you don’t know what that is, I’ll leave you to figure it out.

There is a surprising amount going on if you know what you’re looking for!

A Book Review for Epiphany Sunday

TS Eliot’s poem “Journey of the Magi”

TS Eliot’s poem “Journey of the Magi”

A cold coming we had of it,

Just the worst time of the year

For a journey, and such a long journey:

The ways deep and the weather sharp,

The very dead of winter.’

And the camels galled, sore-footed, refractory,

Lying down in the melting snow.

There were times we regretted

The summer palaces on slopes, the terraces,

And the silken girls bringing sherbet.

Then the camel men cursing and grumbling

And running away, and wanting their liquor and women,

And the night-fires going out, and the lack of shelters,

And the cities hostile and the towns unfriendly

And the villages dirty and charging high prices:

A hard time we had of it.

At the end we preferred to travel all night,

Sleeping in snatches,

With the voices singing in our ears, saying

That this was all folly.

Then at dawn we came down to a temperate valley,

Wet, below the snow line, smelling of vegetation;

With a running stream and a water-mill beating the darkness,

And three trees on the low sky,

And an old white horse galloped away in the meadow.

Then we came to a tavern with vine-leaves over the lintel,

Six hands at an open door dicing for pieces of silver,

And feet kicking the empty wine-skins.

But there was no information, and so we continued

And arrived at evening, not a moment too soon

Finding the place; it was (you may say) satisfactory.

All this was a long time ago, I remember,

And I would do it again, but set down

This set down

This: were we led all that way for

Birth or Death? There was a Birth, certainly,

We had evidence and no doubt. I had seen birth and death,

But had thought they were different; this Birth was

Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death.

We returned to our places, these Kingdoms,

But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation,

With an alien people clutching their gods.

I should be glad of another death.

In this poem TS Eliot gives voice to the mysterious kings who, once they have seen the infant Jesus, return home unable to not completely change their outlook on life and religion. Yet they do not mourn this loss of old certainties, insisting they are happy to be shed of obsolete beliefs. The Magi were led to experience this world-view revolution by the words of a prophet, what Flannery O’Connor called a “realist of distances,” one who can describe in detail what is yet to come because of lucid understanding of what currently is.

In Quaker writer Haven Kimmel’s fictional gem The Used World, Hazel Hunnicutt, proprietor of the eponymous Used World Emporium, is such a prophet. She sees what is distant by discerning the purest essence of what is and urging it into new combinations. Her most significant “arrangement” in the novel, and what drives the plot, involves her two employees: 40-something Claudia Modjeski, a six-foot-four androgynous woman living alone and mourning the death of her beloved mother, and 20-something Rebekah Shook, disowned by her Pentecostal father after she becomes pregnant by her first-ever lover, the decidedly non-Pentecostal Peter. This new arrangement also involves a baby boy, “stolen” after being orphaned into the meth-addicted biker gang Hazel’s own sister has fallen into, as well as a pit bull, abandoned by and rescued from the same.

In Quaker writer Haven Kimmel’s fictional gem The Used World, Hazel Hunnicutt, proprietor of the eponymous Used World Emporium, is such a prophet. She sees what is distant by discerning the purest essence of what is and urging it into new combinations. Her most significant “arrangement” in the novel, and what drives the plot, involves her two employees: 40-something Claudia Modjeski, a six-foot-four androgynous woman living alone and mourning the death of her beloved mother, and 20-something Rebekah Shook, disowned by her Pentecostal father after she becomes pregnant by her first-ever lover, the decidedly non-Pentecostal Peter. This new arrangement also involves a baby boy, “stolen” after being orphaned into the meth-addicted biker gang Hazel’s own sister has fallen into, as well as a pit bull, abandoned by and rescued from the same.

The new story that is created here is ingeniously formed by Kimmel from elements of the old. Narration of the present-day lives of the main characters is interspersed with chronologically presented flashbacks to Hazel’s childhood and early adulthood. In these scenes Hazel, who early in life is “marked” for prescience by an owl, learns to differentiate between those acts that demonstrate pure love – though they might not be socially accepted – and “antique” traditions that deserve casting off when what they produce is pain and suffering. Hazel’s past and present circumstances call for quite challenging acts of discernment, from evaluating her mother’s work with unwanted pregnancies and her own repressed love for her best friend to the proper response to her sister’s addiction and to a fledgling lesbian relationship. Kimmel does not portray these acts of discernment as easy, nor should she. She opens such perennial powder-kegs as illegitimacy, homosexuality, and abortion, all flash-points that persist throughout human history, elicit changing societal responses as humanity evolves, and remain controversial because they are so complex.

The “theological” opinions voiced in the book contrast Rebekah’s father Vernon, a member of The Prophetic Mission where “the cruel, the stupid, the kind and the good alike believed they were the conduits for the direct revelation of Yahweh,” and Amos Townsend, pastor of the Church of the Brethren. The principle difference between these two is the degree of certainty with which they assert their beliefs. Where Vernon Shook continually reaffirms his own incontestable convictions, Amos humbly questions his own claims even from the pulpit. While Amos mistrusts the idea that anyone can thoroughly understand Jesus and so speculates more than pontificates, he does avow those truths he knows to be everlasting, especially the truth that God is Love and is revealed through love.

Throughout the book, in both image and theme, Kimmel contends there is much in life to preserve because it is good, but there is also much that should not be clutched merely because it is old. Acts of loving responsibility, symbolized by Claudia’s mother’s preserves and Rebekah’s mother’s recipes, shine out against the micro-waved meals of Claudia’s married-with-children sister Millie and the immature instant-message romance of the self-centered and two-timing Peter. These two, dubbed the New Mother and the New Man, have left the past completely behind but have also, unfortunately, abandoned those elements that were most worth saving.

On the other hand those who cling too fiercely to their outdated beliefs – Vernon and Hazel’s father Albert – leave destruction in their wake when the “truths” they cling to are divisive, vindictive, self-serving, and intolerant. Those characters unwilling or unable to sort the treasure from the junk are left to suffer at their own hands, while those who adapt and move on, doing what love asks of them, thrive and grow. Kimmel challenges us too to retain what things are true, honest, just, pure, and lovely but to also be open to the new and sometimes unexpected ways these can be combined. The only test, and every great agape practitioner from Saint Francis to Dorothy Day would agree, is the question What is love asking of us now?

Haven Kimmel, whose hysterically funny memoir A Girl Named Zippy launched her onto the New York Times Bestsellers List in 2002, employs the same down-home humor in The Used World. But here in the world of fiction, Kimmel can employ even more nuance in her craft. Her symbolic touch throughout is simultaneously subtle and ever-present. The novel can simply be enjoyed as a gripping tale and yet the watchful reader discovers constant nuggets of pure philosophical gold, just as the persistent antiquer consistently finds new treasures in her favorite store. For example, the epigraph for Part Two from Luke, “the child in my womb leaped for joy,” literally describes Claudia’s reaction to the arrival of the pregnant Rebekah but also posits these two as a modern-day Elizabeth and Mary. Even such Judeo-Christian mainstays as a flood, a mob called Legion, and a woman saltily looking back read as seamless plot elements, especially as they are mixed with non-Biblical archetypes such as an Old Road, animal familiars, and three-headed dogs.

And this is indeed Kimmel’s point. There is only one story, one rock of permanence, one eternal word, and that is compassion. The impermanent and ever-changing face of history’s artifacts should not be worshipped. If the Word Himself calls us to anything it is to caritas, in whatever unusual and unexpected combinations this might require. It could be an illegitimate baby born to country folks in a stable and worshipped by royalty. It could be a woman accepting the love of another woman and raising a stolen child. The Magi say that what looks to be birth turned out to be death. And in The Used World what looks to be death turns out to be birth. The suicidal Claudia, the maltreated infant Oliver, the exiled Rebekah, the frantically despairing Millie and even the still-bereaved Hazel find new life in the odd arrangement a blizzard in Indiana hurls into place. As Hazel says, “There is wild change afoot, and you must be brave enough to not only endure it, but to embrace it, to make it your own.” And to do so, Kimmel maintains, always with compassion.

Cloud and Smoke by Day

This one’s going out to Twenty-First Century Housewife from Wife of the Tasmanian Devil:

At age thirty-five, some kind of genetic gear in Patrick ticked into place and set off a cascade of chemical changes that bound him to his room. Upon waking, the weight of his body and his obligations and of the lowering grey sky pressed him like a torture board covered with rocks. He would stand and feel unbalanced, couldn’t catch his breath, his heart raced and thumped in his chest, he would fall to one side. The only respite was sleep and that was hard to find.

He called in sick for one day, two, three, until finally his wife called the doctor and made an appointment. The medicine took weeks to build up, and in those three weeks, all that he was and all that he was to be were called in for trial. By all accounts he was a success. An accountant, department manager, a home owner, a husband, a dutiful son, an adoptive father. But under the smiling and successful surface a layer of pure marble protected him from the outside. Within that edifice was quiet, protection.

The chemicals swirling now within were corroding that façade from the inside out. He felt chinks missing here and there, on his left side under his arm, on a small patch of his skull, tiny interior pock marks and depressions in the armor that left him vulnerable. And the places became bigger each day, and the fear, coupled with the extraordinary weight of the pain, kept him behind closed doors with the curtains drawn.

The chemicals swirling now within were corroding that façade from the inside out. He felt chinks missing here and there, on his left side under his arm, on a small patch of his skull, tiny interior pock marks and depressions in the armor that left him vulnerable. And the places became bigger each day, and the fear, coupled with the extraordinary weight of the pain, kept him behind closed doors with the curtains drawn.

In his grand home, he crawled to the farthest corner and hid there from the storm that brewed around him. It felt to him as if he was in a huge warehouse, and in the smallest corner of the smallest space, under storage containers and in behind dusty bins, he was a tiny dot in the scheme. No one could see him or find him here, and in the larger world, no one knew of the warehouse, much less his tiny dot within it.

In trembling and oppression he waited for relief. The doctor promised that he would feel a change, but it was slow to come. Loretta forced him each morning to take the tiny pill, which he did, then returned to his room and tried to sleep. Loretta tried to lure him out with yard tasks in the sun, a new grill, a hockey game for the computer. But nothing helped. When Loretta’s son Max came home from school, Pat would rouse himself enough to ask about his day and eat a little dinner, help him with homework, hug Julie.

Finally after three weeks, he felt the weight ease, and he returned to work after a weekend of feeling more like his old self. One afternoon weeks later, at his desk looking at inventory figures, he answered his phone.

“Pat Madden,” he said, still looking at his papers.

“Mr. Madden, this is Connie Bankert, principal at Bridgeport Middle School?”

“Yes. Is Max alright?”

“He’s fine, but there has been an issue and it is essential that I see you here before the end of the day. I have called your wife and she is on her way.”

“What’s the problem?” Pat put down his pen and pulled his date book in front of him.

“It appears that Max threatened an attack on the school and the police were here first thing this morning.”

“Oh, Lord,” Pat sighed. “I can be there at 2:00. Is that soon enough?”

“Yes. We have Max in in-school suspension at the moment.”

“OK. I will call Loretta and we’ll both be there.”

“Thank you, Mr. Madden. Your step-son is in a bit of trouble. I hope we can resolve this amicably.”

“Yes. Thank you.”

Pat hung up the phone and rested his head on his hands. He breathed deeply twice and then picked up the phone and dialed.

“Hello?” Loretta answered.

“Hey.”

“Oh, God, Pat, what is this? What has he done? Someone called the police? I found the damn thing. It’s just a silly note in his notebook. It means nothing. He wouldn’t do that, would he?”

“No, Loretta, of course not. I’m sure it’s all a mistake. Listen, I can’t get out until 2 and I told Mrs. Bankert we’d be there then. Are you OK to drive?”

“Yes, of course. I’ll meet you out front. Are you OK? Any symptoms?”

“No, I feel OK. I’ll see you there.”

Two hours later Pat pulled up in front of the middle school. Loretta was there already waiting in her white Camaro. She got out when she saw Pat pull up behind her. As usual, she looked amazing, thin, stylish, well-dressed. She came to Pat and put her arms around him, rested her head on his shoulder.

“This feels like some kind of curse. First you, now Max. What’s next, your mom or dad?”

“OK, now, don’t overreact. Let’s just see what’s going on.”

In the office, Max sat in one of four chairs in a row. He looked up with fear when they walked in. His long hair fell across one eye and he flipped it out of his way.

“Hey, buddy,” Pat said, putting his hand on his shoulder.

“Hey.”

Mrs. Bankert walked out and motioned Pat and Loretta into her office. Loretta smiled briefly at Max and went in behind Pat and sat down.

“Mr. And Mrs. Madden, thank you for coming in. Let me tell you what I know. At 8:00 this morning Sergeant Walroth of the Bridgeport Police department came here following up on a complaint that was called in. Apparently a girl in one of Max’s classes saw him making a map of the school and plotting out a plan for an attack. She got scared and told her mother that night and the mother called the police.”

“I have the notebook here,” Loretta interrupted. “I found it in his room where he had said it would be.” She opened the notebook on the table. There was a neatly drawn and labeled map of the middle school with various arrows labeled with weapons: tanks, B-52s, AK47s, etc.

“I have the notebook here,” Loretta interrupted. “I found it in his room where he had said it would be.” She opened the notebook on the table. There was a neatly drawn and labeled map of the middle school with various arrows labeled with weapons: tanks, B-52s, AK47s, etc.

“I find this rather disturbing,” Mrs. Bankert said.

Pat pulled the notebook over to him. He studied it carefully. “Tanks? B-52 bombers? Do you think this is serious? Where is a 12-year-old going to get military weaponry?”

“Mr. Madden, I am sure you want to defend your step-son, but after Columbine, we simply must take even a threat – ridiculous or not – as a possibility. I have children’s lives at stake here.”

Pat pushed back his chair and folded his arms across his chest. “Mrs. Bankert, how many years do you have left here? Two, before you retire with a big pension? Don’t you have better things to do than punish a kid who was obviously just being a kid?”

Loretta put her hand on Pat’s arm. “Pat,” she said. “Let’s just hear what Mrs. Bankert has in mind.”

The principal pulled out a piece of paper and passed it to them. It was labeled “Disciplinary Action.”

“Max will be out of school for three days and then in in-school suspension for two. Then he may return to school.”

“OK,” Loretta said quickly. “I think that’s perfectly reasonable, don’t you Pat?”

“And I might also suggest some counseling. Here is a form to take home in case you decide to utilize this service.”

Pat glared and stood up. “I will take my son home now,” he said. He walked out the door.

“Thank you, Mrs. Bankert, and I am sorry about the trouble,” Loretta said.

Pat dropped Max off at the house, after a quiet ride. Loretta followed and brought Max into the house with her arm around him. Pat returned to work. On his way home later, he stopped at his parents’ house. Peggy was not home yet, but Daniel stood with Pat in the kitchen as Pat paced back and forth and back and forth. Everything gathered in his mind, the doubt, the anxiety, the responsibilities, the long slow climb back to normal and now this compression. Daniel tried to talk to him, tried to calm him. Pat was shaking and his teeth were clenched. He could not speak, just periodically shouted meaningless sounds. Finally his hands clenched into fists and with all his might he punched the wall over the old highchair, knocking a hole in the sheetrock. Plaster dust flew everywhere. He tipped his head back and looked at the ceiling and he roared in frustration and grief. Daniel walked over and held his shaking body, held him still, just held him.

Pat dropped Max off at the house, after a quiet ride. Loretta followed and brought Max into the house with her arm around him. Pat returned to work. On his way home later, he stopped at his parents’ house. Peggy was not home yet, but Daniel stood with Pat in the kitchen as Pat paced back and forth and back and forth. Everything gathered in his mind, the doubt, the anxiety, the responsibilities, the long slow climb back to normal and now this compression. Daniel tried to talk to him, tried to calm him. Pat was shaking and his teeth were clenched. He could not speak, just periodically shouted meaningless sounds. Finally his hands clenched into fists and with all his might he punched the wall over the old highchair, knocking a hole in the sheetrock. Plaster dust flew everywhere. He tipped his head back and looked at the ceiling and he roared in frustration and grief. Daniel walked over and held his shaking body, held him still, just held him.

Pat knocked, and entered Max’s room when he heard a mumbled assent. Max lay on his bed face down. His music was playing and his books and notebooks were sprawled over his bed, spilling down onto the floor. Pat sat at the edge of his bed and considered Max’s long straggly hair.

“Max?”

“Mmmmm.”

“How are you doing, man?”

“I don’t know.”

“It was a joke wasn’t it.” Pat stated this. “Just a joke.”

“Yeah,” through the pillow. “Nobody was supposed to see that and anybody who knows me would know it was just a joke.”

“But Mrs. Bankert doesn’t know you. She might have thought you were serious.”

“I guess.” Still spoken into the pillow. “Is Mom mad?”

“She’s concerned, about you. She doesn’t want this to ruin your year. You were off to a good start.”

Pat had been helping Max every night with his math and science. It came hard to him, but Pat sat, patiently, and helped him with each problem while Loretta cooked Italian dishes – gnocchi and rigatoni and calzone. Pat loved her Italianness. She was so different than his sisters or cousins, so loud and bright and passionate.

“Are you mad? Are you going to leave? Are you going to go back into your room?”

“No, I got some help with that. I’m OK now, and as far as leaving, it would take a lot more than a psychotic plot to blow up Bridgeport Middle School to scare me off.”

Max turned his head slightly to check for the joke and smiled a little.

“I thought of doing that myself years ago.” Pat rubbed his hand across his thinning hair. “Max, I chose you, man. I chose to adopt you and Julie both – I didn’t have to. If this is tough, buddy, I’m going through it with you. If it hurts you, it’s going hurt me and your mom, too. But we’ll all hurt together.”

Max turned his face, and Pat could see he had been crying.

“I’m sorry, Pat. You’ve done a lot for me and I screwed up by doing something stupid.”

“Hey, we all do something stupid at some point. If this is the worst you do, count yourself lucky.”

“I bet you never did anything this stupid.”

“Yeah, I did.”

Max looked at him, waiting.

“I was once at a hockey game, and I was in the restroom, and this guy, this drunk guy, put out a cigarette on my arm. I got so mad that I punched him in the nose and broke it. And I didn’t stop then, I kept going and the police had to pull me off. Then I got arrested and my dad had to come and bail me out.”

“Whoa,” Max said sitting up. “Remind me not to mess with you.” Max wiped his hair off his face with his two hands. “I guess I didn’t do anything like that.”

“At least you only threatened to do something.”

Max looked down at his hands and picked at a hangnail.

“You want to get rid of that thing?” Pat asked.

Max looked up. “What thing?”

“Well, you’ll have to serve your suspensions, but I don’t think we need that map hanging around.”

Max’s eyes widened and then he raised his eyebrows and smiled tentatively.

Max and Pat walked past Loretta in the kitchen and out onto the patio. She looked and smiled but turned back to her stove. Julie was watching a show on TV. It was an early fall evening and still warm. A few leaves fell and drifted down from the big maples on the sides of their manicured lawn. Loretta grew roses, and a few late varieties were still in bloom. Fieldstones walled in the yard in which the grass was perfect, green and lush. Pat and Max took turns with the weekly mowing, Pat one time and Max the next.

Pat walked across the deck and opened the top of the grill. He pulled the map from his pocket and handed the map and matches to Max. Max opened the folded paper, looked at the map, and then laid it on the old coals. He opened the box, took out a match and closed the box again. He lit a match, and the flame hissed and then glowed steady. He held the flame to the edge of the paper and it caught. The paper blackened in a circle at the corner and then burst into orange and yellow, gathering strength until flames shot up into the increasing dusk. The paper curled and charred and shrunk and broke into cloth-like shreds. Pat and Max watched together as one soft piece floated up in the heat column, spiraled slowly, and soared away into the orange sky.

Pat walked across the deck and opened the top of the grill. He pulled the map from his pocket and handed the map and matches to Max. Max opened the folded paper, looked at the map, and then laid it on the old coals. He opened the box, took out a match and closed the box again. He lit a match, and the flame hissed and then glowed steady. He held the flame to the edge of the paper and it caught. The paper blackened in a circle at the corner and then burst into orange and yellow, gathering strength until flames shot up into the increasing dusk. The paper curled and charred and shrunk and broke into cloth-like shreds. Pat and Max watched together as one soft piece floated up in the heat column, spiraled slowly, and soared away into the orange sky.

From “Winter Barley” by Andrea Lee

The Storm

Night; a house in northern Scotland. When October gales blow in off the Atlantic, one thinks of sodden sheep huddled downwind and of oil cowboys on bucking North Sea rigs… even a large solid house like this one feels temporary tonight, like a hand cupped around a match. Flourishes of hail, like bird shot against the windows; a wuthering in the chimneys, the sound of an army of giants charging over the hilltops in the dark…

Halloween

Bent double, Edo and Elizabeth creep through a stand of spindly larch and bilberry toward the pond where the geese are settling for the night. It is after four on a cold, clear afternoon, with the sun already behind the hills and a concentrated essence of leaf meal and wet earth rising headily at their footsteps – an elixir of autumn… Now from the corner of the grove, Edo and Elizabeth spy on two or three hundred geese in a crowd as thick and racuous as bathers on a city beach: preening, socializing, some pulling at sedges in the water of the murky little pond, others arriving from the sky in unraveling skeins, calling, wheeling, landing….

A tumult of wind and dogs greets them as they pull up ten minutes later to the house. Dervishes of leaves spin on the gravel … Both Elizabeth and Edo stare in surprise at the kitchen windows, where there is an unusual glow. It looks like something on fire, and for an instant Edo has the sensation of disaster – a conflagration not of this house, nothing so real, but a mirage of a burning city, a sign transplanted from a dream…

Elizabeth sees quite clearly what Nestor and his cousins have done and, with an odd sense of relief, starts to giggle. They’ve carved four pumpkins with horrible faces, put candles inside, and lined them up on the windowsills… “It’s Halloween,” she says, in a voice pitched a shade too high…[Edo] hurries inside, telling her to follow him.

Instead, Elizabeth lets the door close and lingers outside, looking at the glowing vegetable faces and feeling the cold wind shove her hair back from her forehead… she thinks of a Halloween in Dover when she was eight or nine and stood for a long time on the doorstep of her own house after her brothers and everyone else had gone inside. The two big elms leaned over the moon, and the jack-o’-lantern in the front window had a thick dribble of wax depending from its grin…She’d stood there feeling excitement and terror at the small, dark world she had created around herself simply by holding back.”

I went through a series of many years when I snatched The Best American Short Stories volumes off the New Books shelf at the library as soon as they arrived. Now, not so much. The 1993 edition came out in the midst of my Louise Erdrich jag, and since she was editor that year, I very much snagged and devoured. I was VERY struck by the short story “Winter Barley” by Andrea Lee, not so much for the plot but for the setting and the mood.

A week ago I made the very old librarian go down and retrieve 1993 for me from the basement (I offered to go down there myself, but that is where the very secret books are kept, like A House Like a Lotus by Madeleine L’Engle. What? because of the lesbianism?) and I reread this story and was again transported. This story has taken the place of Mr. McFadden’s Halloween* and The Halloween Tree in my repertoire of seasonal , transporting books. So above are my favorite chunks with some visuals to go along.

This story was originally published in The New Yorker and can be read (if you are a digital subscriber) here.Or you can get the 1993 edition of The Best American Short Stories. Here is the New Yorker’s abstract:

“Elizabeth, 30, a banker from Massachusetts who is stationed in Rome, and Edo, 60, an exiled prince from an Eastern European kingdom now extinct, have an affair at his home in Scotland. They meet at Easter. Elizabeth is invited to Scotland by Edo’s gay nephew, Nestor, her neighbor in Rome. Nestor doesn’t show up, having deliberately planned to throw the two of them together. Edo regales her with anecdotes about his world travels, and challenges her with his snobbery. They become lovers, although Elizabeth does not feel that she is in love with Edo. She is bored by his interest in water fowl; he has designed his estate to attract them. At Halloween, Nestor and two aristocratic friends arrive in Scotland. They and Edo try to offend Elizabeth with bawdy songs and stories. Edo is annoyed when the young men surprise him and Elizabeth by putting jack-o’-lanterns in the windows. Elizabeth has a childhood memory of Halloween in Dover, Massachusetts. Edo recalls an experience in Persia, when two of his friends, Persian princes, surprised him in the desert, bearing falcons.”

According to Andrea Lee’s Contributor’s Note in BASS, she was inspired by a line at the end of King Lear where Lear and Cordelia plan to escape together and enjoy “an improbable idyll” of father-daughter love. Lee wanted to replicate such an idyll in a modern context and so devised a “father-daughter” love affair. Why did an image of Michael Douglas and Catherine Zeta-Jones just jump into my head?

According to Andrea Lee’s Contributor’s Note in BASS, she was inspired by a line at the end of King Lear where Lear and Cordelia plan to escape together and enjoy “an improbable idyll” of father-daughter love. Lee wanted to replicate such an idyll in a modern context and so devised a “father-daughter” love affair. Why did an image of Michael Douglas and Catherine Zeta-Jones just jump into my head?

Ray Bradbury's painting of The Halloween Tree

Happy Halloween, everyone!

* Speaking of Rumer Godden, I have lately discovered her adult novels. (I was a huge fan of her middle grade books: Mr. McFadden’s Halloween, The Doll‘s House, The Story of Holly and Ivy, Miss Happiness and Miss Flower, The Kitchen Madonna). I am now enjoying In This House of Brede about Benedictine nuns. Next on my list is Five for Sorrow, Ten for Joy. Both of these are part of the Loyola Classics series. More on that later. Check her out at left with her cats. The website for the Rumer Godden Literary Trust is wonderful.

* Speaking of Rumer Godden, I have lately discovered her adult novels. (I was a huge fan of her middle grade books: Mr. McFadden’s Halloween, The Doll‘s House, The Story of Holly and Ivy, Miss Happiness and Miss Flower, The Kitchen Madonna). I am now enjoying In This House of Brede about Benedictine nuns. Next on my list is Five for Sorrow, Ten for Joy. Both of these are part of the Loyola Classics series. More on that later. Check her out at left with her cats. The website for the Rumer Godden Literary Trust is wonderful.

The Catcher in the Rye

For your listening pleasure while you are reading this post, here is the Count Basie Band (my dad’s favorite) playing Comin’ Through the Rye.

This is a photograph of my maternal grandmother, Mabel Ruth Kellick, in her teens. Whenever she showed me this photo, she would always say, “Mabel, coming through the rye.”

One of my three books waiting to get published (Who am I kidding? I am waiting for an agent to discover me and wrangle one of them into something salable) is called “Wonderful Plans of Old.” It starts with a family intervention to deal with the father’s alcoholism, and then goes backwards and forwards in time to explore the roots of this moment as well as the effects after it. When I was writing it, I was reading the Book of Isaiah, because it seemed to fit so well with the ideas of Desolation and Redemption I was exploring in the book, and each chapter title is taken from Isaiah. This chapter is from the very middle. Don’t worry: I will be tying all this seemingly random stuff together!

Among Fat Ones, Leanness

Kate was gone to China – we rarely heard from her. Patrick was home sometimes, six weeks at college followed by six weeks of working at home. And I was a high school senior: pianist, valedictorian, tennis team captain, and so very alone. My English class read The Catcher in the Rye that year, and like all adolescents I felt that Holden Caufield was my voice: repulsed by all the phoniness of adulthood and reluctant to move into the contradictions it seemed to mandate.

I rode the bus home from school, sitting in the front seat with a scarf over my nose and mouth to filter out the smoke – not all of it tobacco – that drifted from the back of the bus. Our driver was known to allow – even condone – smoking, so the bus was packed with students willing to walk ten blocks home from the wrong stop to smoke their pot in warmth for one mile. Roxie the bus driver would snap her gum, big ball earrings bobbling, and cackle to the back, “You smokin’ that horse shit back there?” She purposely aimed for the big bump halfway down Washburn Street and we would all fly into the air. Everyone but me laughed.

When I got dropped off, I walked across the street, got the spare key from the garage, and let myself in. No one was home. I’d drop my books at the kitchen table, take off my coat, and start the ritual. Holden had a malted and grilled cheese at the soda fountain. Without the equipment of a diner, I made do with a cheese sandwich on toast and a chocolate milkshake. Then I would line up twenty-five Ritz crackers – five by five – and slather them with peanut butter. Once I had eaten those, I checked into the ice cream – usually half of a half gallon would go next. Then Oreos: one column. By then my stomach felt tight, way beyond Holden and into a territory of loneliness Holden did not know, a territory where no one saw me, no one knew what I was doing, where no one seemed to notice that I was home, wanting someone to care about my day, wanting someone to notice that I had emotionally quit everything.

The upstairs bathroom was the place: away from anyone, close the door, turn on the fan, run the water, pretend I was a teenage girl obsessed with washing my face in case anyone got home early. No one knew – or really cared – what I was doing, even when I repeated this part of the ritual right after dinner. It really became quite easy. I would drink an enormous glass of water, and then it was amazing how easily it all came out – it didn’t even taste bad, just a watered down version of what I had just eaten. Three times and it was all out. I had had the feast – treated myself if no one else would – and still did not gain weight – as thin as a Junior Miss at least. So thin that my period stopped and Mom finally took me to an endocrinologist who took one look at me and said, “She’s too thin.”

I got thin, very thin, and I would lie in the hot June sun in the driveway on the lawn chair wearing only the Bloomies underwear and camisole I had bought on a class trip to New York City, the camisole rolled up to expose my browned stomach. I had no bikini and Mom wouldn’t allow one, but my blue-and-pink-striped cotton undies worked the same, as long as I had covered up by the time Mom got home. Our backyard was shaded by a huge maple, but there was a strip of strong sunlight along our driveway right next to the Gardiner Girls’ lilac bushes, which were on the other side of the waist-high chain link fence.

Mrs. Dixon came over one day and found me this way. I didn’t hear her approach since I had my Walkman on, slathering myself with coconut oil. “It must be nice to be so perfect,” she said, looking down her nose at me. She obviously disapproved of a teenage girl half dressed lying in view from Morton Avenue, or else she was jealous – a former beauty queen herself, believe it or not – whose figure with teenage children now was not what it had been.

I smiled in a knowing adolescent way and pulled my sunglasses back down over my eyes. If only boys would have the same response, but my obsession with my weight was mixed with a fear of sex, and the physiological effects of thinness had been to halt my hormones, leaving me desireless. I craved the jealousy of my female peers more than attraction by males. I wouldn’t have known what to do with a boyfriend if I had one.

The night of my first drink, I had gone to a senior dinner dance with a childhood pal, and there, in a funky bar in Buffalo, I had several white Russians. They tasted good, and I enjoyed, for a time, the way I warmed up, chatted with everyone, danced without inhibitions. But on the way home I felt bad, guilty, headachy, and when I crashed into my room that night, I planned the next morning to confess and gain absolution from my parents.

When I finally awoke, a beautiful, sunny spring day, my head ached, and I lumped down the stairs to the kitchen where my father was making a second pot of coffee. I slumped into a chair and drank the glass of orange juice he offered.

“How was the dance?”

“OK, I guess.”

“Did Jeremy behave?”

“Barely.” I finished the orange juice and poured some more.

“Where’s Mom?” I asked. “Aren’t you guys going to church?”

Dad sat down across from me and took a deep breath, sighed long.

“Mom’s upstairs in her room.”

I looked up. Something had happened.

“She had to have her stomach pumped last night.” I stopped. I had a vision of an ambulance in the driveway, reds lights flashing on the neighbors’ houses and on the Sansones’ garage wall. Mom on a gurney coming out the front door.

“She … wanted to show me what I looked like, so she drank an entire bottle of wine.”

I felt sick to my stomach. “Is she OK?”

“Yes. She’s going to be OK. She’s resting upstairs.”

“Can I go see her?”

He nodded.

I got up, holding my throbbing head, and went into the living room and up the stairs to the second floor. Across the hall I could see that the door of the sewing room where she had been sleeping of late on the spare bed was shut. I approached it quietly and peeked in through the crack. She had her eyes closed, but she heard me at the door and opened them.

“Hi, Moll. You can come in.”

I opened the door, which squeaked a little, and closed it behind me. The lovely soft sun had risen and came in a strip under the shades on the east window. I moved slowly to the bed and sat down on the edge.

“How are you feeling?” I asked.

“Kind of bad,” she whispered. “Did Dad tell you?”

“Yes.”

“I’m sorry. On the night of your date.” She cleared her throat, which appeared to be a painful process. “How was it?”

“It was fine. Do you need anything?”

“No.”

“Can I lie down with you?” She made room, turned over and faced the wall. I lay down on top of the blanket and spooned in next to her, like she used to do with me when I was scared by a nightmare, but our positions were reversed. I put my arm around her and just stayed. The shade glowed with the sunlight outside, but in her darkened room it felt more like sunset.

She was there through the next two weeks, up until my graduation. Dad called and told her boss that she was very sick. After school I would come home and lie with her. Then I would go back downstairs and sit at the table, doing my homework: Calculus, AP Bio, English, Psych – a breeze really, it just took time – and maybe I would play the piano, or practice my valedictory address, or I would take the car and drive to the school a few blocks away and practice my forehand, hitting my tennis ball against the big brick wall, over and over and over and over until blisters formed and broke open and my hands bled.

Did the music end? Here it is again.

Did the music end? Here it is again.

I would not wish such a senior year on my worst enemy. Unfortunately, many students in high school DO have this kind of senior year. I have been teaching seniors now for eleven years, and I am convinced that it is one of the most stressful and difficult years of a kid’s life. It is like Kindergarten in reverse. Kindergarten means leaving the safety of home for the unknown of school; senior year involves leaving not only the now thoroughly known of school, but also leaving hometown, everyone known and loved for 18 years of life, and heading into the unknown of adult life.

Yes, some students are Homecoming King or Queen and apply early decision and are accepted at their first choice college, with a happily married mom and dad standing proudly behind them. But plenty of others are dealing with a parent’s illness or divorce or a major family problem, they have suffered socially throughout school and are glad to be leaving it behind, though they are simultaneously terrified of the blank slate before them. Sometimes no one has ever seen or understood their situation, and they have no support at all as they apply to colleges, all the while knowing that there is no money available at home to support this huge and expensive venture.

These kids need a catcher in the rye. They are technically adults, and yet many of them are running dangerously close to a cliff’s edge. Oddly enough, I have found myself in a job where I can BE the catcher in the rye for some of these kids. In my previous teacher job, I saw 75 kids a day for 40 minutes each: they were a blur. Because I now have a small class of students and see them for over two hours a day, my relationship with them is very intense and becomes very close. I know their lives and their dreams. Also, the programs that my colleagues and I run require students to leave the safety and familiarity of their home schools and take an early leap into independence and novelty. We often end up with the kids who are happy to be leaving their high schools behind.

These kids need a catcher in the rye. They are technically adults, and yet many of them are running dangerously close to a cliff’s edge. Oddly enough, I have found myself in a job where I can BE the catcher in the rye for some of these kids. In my previous teacher job, I saw 75 kids a day for 40 minutes each: they were a blur. Because I now have a small class of students and see them for over two hours a day, my relationship with them is very intense and becomes very close. I know their lives and their dreams. Also, the programs that my colleagues and I run require students to leave the safety and familiarity of their home schools and take an early leap into independence and novelty. We often end up with the kids who are happy to be leaving their high schools behind.

Because I was also one of these types, I find myself with a rare ability to see their fears and their hurts, and I find myself so grateful to be in a position to help them, to the best of my ability. To quote Holden, my main man,

“I keep picturing all these little kids playing some game in this big field of rye and all. Thousands of little kids, and nobody’s around – nobody big, I mean – except me. And I’m standing on the edge of some crazy cliff. What I have to do, I have to catch everybody if they start to go over the cliff – I mean if they’re running and they don’t look where they’re going I have to come out from somewhere and catch them. That’s all I’d do all day. I’d just be the catcher in the rye and all. I know it’s crazy, but that’s the only thing I’d really like to be. I know it’s crazy.”

Not crazy, Holden. I hear you, dude. Many of us have fallen off that cliff because no one was there to catch us. But anyone who has been over that cliff can see – preternaturally almost – those heading toward the edge. You can see it in their eyes, in their stance, in their words or their silence. If you personally survive the fall and pick yourself back up, you are in a unique position to see those little kids nearing the edge and to try to get in the way.

My heart aches for the Holdens and the Mollys of the world, and the many real teenagers I have seen undergo this process. My heart aches because it ached for me going through it. Holden sobs for Phoebe in her joy on the carousel, and it is true that innocence – either in its still pure form or lost through no fault of the child – is worth our sobbing over. The events that cause this are often beyond anyone’s control; who can stop cancer or death or any of a variety of things from raining on our parades? But I wish here to offer thanks that I have been given the opportunity to see and assuage what pain I can. God grant me the wisdom and the strength to do so.

Carousel by Leeanne McDonough as found at http://dazzioart.com/

Autumn in Central New York State

It was the sweetest time of the year, she thought. Coming home from the gallery, over the hills through Edmeston and New Berlin, she had watched the sallow final green of the fields go ocher; she had seen the brush, under a silky darkening sky, turn sere. The sumac was brilliant with its final burn. The wind, though still warm with late September, had a touch to it of October’s chilled-wine autumn taste. And here she was in a bulky sweater and jeans and her boat shoes, walking behind the house and sipping at the wind…

It was the sweetest time of the year, she thought. Coming home from the gallery, over the hills through Edmeston and New Berlin, she had watched the sallow final green of the fields go ocher; she had seen the brush, under a silky darkening sky, turn sere. The sumac was brilliant with its final burn. The wind, though still warm with late September, had a touch to it of October’s chilled-wine autumn taste. And here she was in a bulky sweater and jeans and her boat shoes, walking behind the house and sipping at the wind…

The garden behind the house, a hundred by a hundred feet or so, still held the heat of the day. She kneeled in the friable soil that she’d worked, manured, nourished, rotary-tilled, and weeded for years, and she stayed that way, on hands and knees, looking into the low sun. The green mulching plastic she hated but used because it kept down the weeds now caught the sunlight, and the garden looked striped into rows of rich earth and rows of shiny green liquid. The dark tomato vines on their green bamboo stakes were drooping with the weight of plum tomatoes she hadn’t ye plucked. Most were dark red, and even going soft.

There were hundreds to take, and although she hadn’t planned to harvest tonight, the low orange sun, the sky that looked like a dark – an African – skin, and the smell of the vines, that luxuriance of greenness, made her take off her sweater and, with goose bumps pricking the flesh of her arms and her neck, tie its sleeves together and fill it with all the dry, firm tomatoes she could fit inside its upside-down torso…

There were hundreds to take, and although she hadn’t planned to harvest tonight, the low orange sun, the sky that looked like a dark – an African – skin, and the smell of the vines, that luxuriance of greenness, made her take off her sweater and, with goose bumps pricking the flesh of her arms and her neck, tie its sleeves together and fill it with all the dry, firm tomatoes she could fit inside its upside-down torso…

There were days when the light and temperature made you want a sweater on not so much because you were chilly as because the day or evening looked like chill, suggested that being a little cold would be appropriate, and you wore something heavy, to acknowledge the world: Canada geese overhead, out of sight but hooting the shrill sad cries; the sky going one tone darker of blue; the roadside milkweed bobbing in a wind that would bring enough col within the week, she thought, to burst them into white silk hairs and crusty brown shell.

There were days when the light and temperature made you want a sweater on not so much because you were chilly as because the day or evening looked like chill, suggested that being a little cold would be appropriate, and you wore something heavy, to acknowledge the world: Canada geese overhead, out of sight but hooting the shrill sad cries; the sky going one tone darker of blue; the roadside milkweed bobbing in a wind that would bring enough col within the week, she thought, to burst them into white silk hairs and crusty brown shell.

From Harry and Catherine by Frederick Busch

OK, I’ll admit that my adoration of this book is very far beyond normal. First, it is set RIGHT in my neck of the woods – I drive through Edmeston and New Berlin on a regular basis – so it makes my sometimes hum-drum life seem quite romantic. SECOND, I met Fred Busch, who was a professor at Colgate just to the north AND the founder of the Colgate Writers Workshop AND a phenomenal writer. His wife Judy was a mentor of mine when I first started teaching, and as Fred says in the dedication, This is Judy’s book. LAST, I think Catherine Hollander is just a kick-butt heroine, and I really jam to her artisty wood-chopping tomato-picking 40-something mother-of-boys Gestalt.

OK, I’ll admit that my adoration of this book is very far beyond normal. First, it is set RIGHT in my neck of the woods – I drive through Edmeston and New Berlin on a regular basis – so it makes my sometimes hum-drum life seem quite romantic. SECOND, I met Fred Busch, who was a professor at Colgate just to the north AND the founder of the Colgate Writers Workshop AND a phenomenal writer. His wife Judy was a mentor of mine when I first started teaching, and as Fred says in the dedication, This is Judy’s book. LAST, I think Catherine Hollander is just a kick-butt heroine, and I really jam to her artisty wood-chopping tomato-picking 40-something mother-of-boys Gestalt.

If you like this novel, there are two short stories that I know of that precede it, found in Domestic Particulars and Too Late American Boyhood Blues. (If anyone knows of other Harry and Catherine stories I missed, please let me know.) If you like books, read everything Fred Busch ever wrote because he was brilliant. I just ordered three used copies of his novel Sometimes I Live in the Country to foist onto my students from Sherburne because it is set in their school. I have read Harry and Catherine probably 15 times.

If you like this novel, there are two short stories that I know of that precede it, found in Domestic Particulars and Too Late American Boyhood Blues. (If anyone knows of other Harry and Catherine stories I missed, please let me know.) If you like books, read everything Fred Busch ever wrote because he was brilliant. I just ordered three used copies of his novel Sometimes I Live in the Country to foist onto my students from Sherburne because it is set in their school. I have read Harry and Catherine probably 15 times.

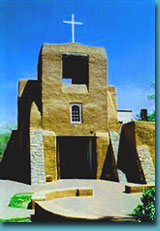

Writing in the desert, an adobe study

I think that Death Comes for the Archbishop is my end-of-August read because the lovely painting on the cover of my copy is filled with blues and yellows and oranges, the colors of late summer/early autumn. Also, there is something about returning to teaching that calls up what little Bishop Latour I have in me. And of course, woodsmoke. If you have never read this book, don’t let the title dissuade you. Only the last, very-short chunk deals with his death. Most of the book is very lively and uplifting.

…the Bishop sat at his desk writing letters … Father Latour had chosen for his study a room at one end of the wing. It was a long room of agreeable shape. The thick clay walls had been finished on the inside by the deft palms of Indian women, and had the irregular and intimate quality of things made entirely by the human hand. There was a reassuring solidity and depth about those walls, rounded at door-sills and window-sills, rounded in wide wings about the corner fire-place. The interior had been newly whitewashed, and the flicker of the fire threw a rosy glow over the wavy surfaces, never quite flat, never a dead white, for the ruddy colour of the clay underneath gave a warm tone to the lime wash. The ceiling was made of heavy cedar beams, overlaid by aspen saplings, all of one size, lying close together like the ribs in corduroy an clad in their ruddy skins. The earth floor was covered with thick Indian blankets; two blankets, every old, and beautiful in design and colour, were hung on the walls like tapestries.

…the Bishop sat at his desk writing letters … Father Latour had chosen for his study a room at one end of the wing. It was a long room of agreeable shape. The thick clay walls had been finished on the inside by the deft palms of Indian women, and had the irregular and intimate quality of things made entirely by the human hand. There was a reassuring solidity and depth about those walls, rounded at door-sills and window-sills, rounded in wide wings about the corner fire-place. The interior had been newly whitewashed, and the flicker of the fire threw a rosy glow over the wavy surfaces, never quite flat, never a dead white, for the ruddy colour of the clay underneath gave a warm tone to the lime wash. The ceiling was made of heavy cedar beams, overlaid by aspen saplings, all of one size, lying close together like the ribs in corduroy an clad in their ruddy skins. The earth floor was covered with thick Indian blankets; two blankets, every old, and beautiful in design and colour, were hung on the walls like tapestries.

On either side of the fire-place, plastered recesses were let into the wall. In one, narrow and arched, stood the Bishop’s crucifix. The other was square, with a carved door, like a grill, and within it lay a few rare and beautiful books. The rest of the Bishop’s libray was on open shelves at one end of the room.

The desk at which the Bishop sat writing was an importation, a walnut “secretary” of American make. The silver candlesticks he had brought from France long ago. They were given to him by a beloved aunt when he was ordained.

The desk at which the Bishop sat writing was an importation, a walnut “secretary” of American make. The silver candlesticks he had brought from France long ago. They were given to him by a beloved aunt when he was ordained.

The young Bishop’s pen flew over the paper, leaving a trail of fine, finished French script behind in violet ink.

“My new study, dear brother, as I write, is full of the delicious fragrance of the pinon logs burning in my fireplace. (We use this kind of cedar-wood altogether for fuel, and it is highly aromatic, yet delicate. At our meanest tasks we have a perpetual odor of incense about us.)”

The Bishop laid down his pen and lit two candles with a splinter from the fire, then stood dusting his fingers by the deep-set window, looking out at the pale blue darkening sky. The evening-star hung above the amber afterglow, so soft, so brilliant that she seemed to bathe in her own silver light. Ave Maria Stella, the song which one of his friends at the Seminary used to intone so beautifully; humming it softly he returned to his desk and was just dipping his pen in the ink when the door opened…

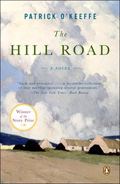

Blogging: The Introvert’s Ultimate Yop!

I recently finished reading Patrick O’Keeffe’s collection The Hill Road, named after the first of the four novellas it contains. I was entranced. O’Keeffe is a professor of Creative Writing at Colgate and was the instructor for the short fiction workshop at the Colgate Writers’ Conference I attended. I had the good fortune of hearing him read from a new work and then meeting him afterwards on the last full day of the conference.

I recently finished reading Patrick O’Keeffe’s collection The Hill Road, named after the first of the four novellas it contains. I was entranced. O’Keeffe is a professor of Creative Writing at Colgate and was the instructor for the short fiction workshop at the Colgate Writers’ Conference I attended. I had the good fortune of hearing him read from a new work and then meeting him afterwards on the last full day of the conference.

I bought his book after the reading, partly because I loved the cover painting called Cottages of Connemara.Two years ago, when I workshopped my novel Wonderful Plans of Old, my group’s favorite chapter was one in which I had imagined an evening in the life of my Irish great-grandparents, and I had set it outside Connemara in Ireland. I have never been to Ireland, nor while I was growing up did I ever hear stories of life in Ireland before my ancestors emigrated. For that matter, I never heard stories of my father’s childhood here in New York. He NEVER spoke about it, leaving me to conjure what I could out of references, imagination, questions, pictures.

What struck me so about O’Keeffe’s collection was how each of the four novellas dealt with this very issue: the task of trying to piece together a story which had never been told, or was only told in snatches under influence of drink or grave illness, leaving me wondering if this trait of Not Talking is endemic in the Irish people. Think of Alice McDermott’s novel Charming Billy, the twisting, winding story of a lie and its truth which had been kept long secret.

Is this tendency Irish? Is it a defense mechanism for any group that has withstood great hardship and dire acts taken out of necessity or despair? Is the same true of Holocaust survivors? former soldiers? Are there certain experiences that are simply too painful for the psyche to bear telling?

My dad after my wedding, Zeke in the background

Or perhaps the common link, one which ties me to my father, is the Irish tendency toward contemplation. My father’s most characteristic pose was standing with weight on one foot, the other resting in front at an angle or up on something, one hand in pocket, the other leaning on a counter or windowsill, gazing. He would spend long periods of time this way. He did not speak much, but I learned to listen very intently when he did speak, for what he had to say was well worth listening to, forged as it was out of these long periods of contemplation.

My dad was an introvert, which is probably why he wanted to become a writer. He had plenty to say, he just didn’t like to talk. I am the same way. In seventh grade, my Home Economics teacher was Mrs. Williams, a.k.a. “Wimp Williams” because she was so soft-spoken. The most upset she ever got was when we were sewing and students would slam down the presser foot on the sewing machines. She would close her eyes, hold out one raised hand in gentle protest, and say with valiantly restrained anger, “Don’t. Slam. the Presser Foot.” And then we would all keep doing it. (I am really sorry, Mrs. Williams).

She told my parents at a parent/teacher conference that she could see I was “keeping my light under a bushel.” When I heard this, I thought to myself, No, I am just not about to cast my pearls before swine. The problem was that if I actually verbalized what I was thinking, my classmates would have thought me even stranger than they already did. It’s not that the teenaged swine would snout my pearls around in the muck but that it would be ME – my deepest self – that they were knocking through the crap. More emotional pain? Nein, danke.

Also, I truly do not like to talk. The physical act of getting my thoughts to slow down enough to verbalize them, of pushing these ethereal things out through the thick clay of my tongue and lips, and not being able to edit words that have floated out into the air, makes talking one of the last things I like to do. I’d rather write.

Thus my gratitude for the tremendous gift of blogging, and I am guessing this is the case for many introverted bloggers. We’ve got things to say. We’ve got thoughts worth sharing. And we are not afraid to cast them out over the wide waters of the internet. But let it be just my WORDS, in print, no sign of me, my face, my squeaky weird voice.

And not only that, but blogging is also ART. You create a visual product with colors and pictures and even MOVIES. It is like my thoughts – both word and image – incarnated digitally.

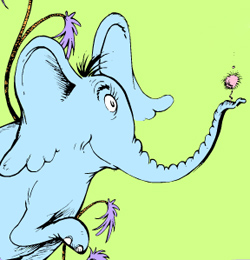

Like the little Who whose “Yop!” finally stops those awful monkeys from boiling that dust speck, introverts need a lot of effort to make noise, but we will do it. And in our long periods of thoughtfulness, we sometimes come up with ideas from which other people can benefit. So, what do I write when I write? I tell my thoughts. I tell the secrets of my childhood. I tell the secrets of my marriage. This is beyond Yop! This is doing what I was raised not to do.

Like the little Who whose “Yop!” finally stops those awful monkeys from boiling that dust speck, introverts need a lot of effort to make noise, but we will do it. And in our long periods of thoughtfulness, we sometimes come up with ideas from which other people can benefit. So, what do I write when I write? I tell my thoughts. I tell the secrets of my childhood. I tell the secrets of my marriage. This is beyond Yop! This is doing what I was raised not to do.

Any child of an alcoholic grows up with the unstated but implicit rule “Don’t tell.” Don’t tell what happens at home. Don’t say how you really feel because no one is really there to hear you. But I have learned, against my familial tendencies, to “tell tales.” Why? First, because I have experienced how silence harms: how not speaking, not communicating your shame or fear or anxiety can cause real damage.

Perhaps I read so much as a kid because in authors I found the words to describe what I was not allowed to say out loud, what I never heard anyone one else say out loud, what was difficult for me to say out loud. And hearing from someone else, in another place, thoughts that I had had, made me see I was not alone, I was not so strange, that there were others out there with similar thoughts and problems and ideas.

Last week I was thinking about this in church and we sang this song:

A lovely painting by blogging artist Jennifer Katheiser

I myself am the bread of life.

You and I are the bread of life.

Taken and blessed,

broken and shared by Christ

that the world might live.

Lives broken open,

stories shared aloud,

becomes a banquet,

a shelter for the world:

a living sign of God in Christ.

This is the second reason I tell my tales. If this is what we are to be – broken and shared that others might live – then the introvert is obligated to share what she is and what she has: her thoughts, her life, her stories, not as recrimination but as a banquet, an offering of those thoughts and experiences in order to console others by letting them see in print their own deepest and perhaps un-worded thoughts. At least that is what I hope to do, give voice to all those weird and profound and silly thoughts that too many people keep under a bushel.

So thanks, all you blogging introverts out there who are letting your voices be heard, and thanks, WordPress, for letting me Yop! Reader, if you find any pearls here, please help yourself, and feel free to cast your own pearls as comments.